About Dan: I'm a computational data journalist and programmer currently living in Chicago. Previously, I was a visiting professor at the Computational Journalism Lab at Stanford University. I advocate the use of programming and computational thinking to expand the scale and depth of storytelling and accountability journalism. Previously, I was a news application developer for the investigative newsroom, ProPublica, where I built ProPublica's first and, even to this day, some of its most popular data projects.

You can follow me on Twitter at @dancow and on Github at dannguyen. My old WordPress blog and homepage are at: http://danwin.com.

How to automatically timestamp a new row in Google Sheets using Apps Script

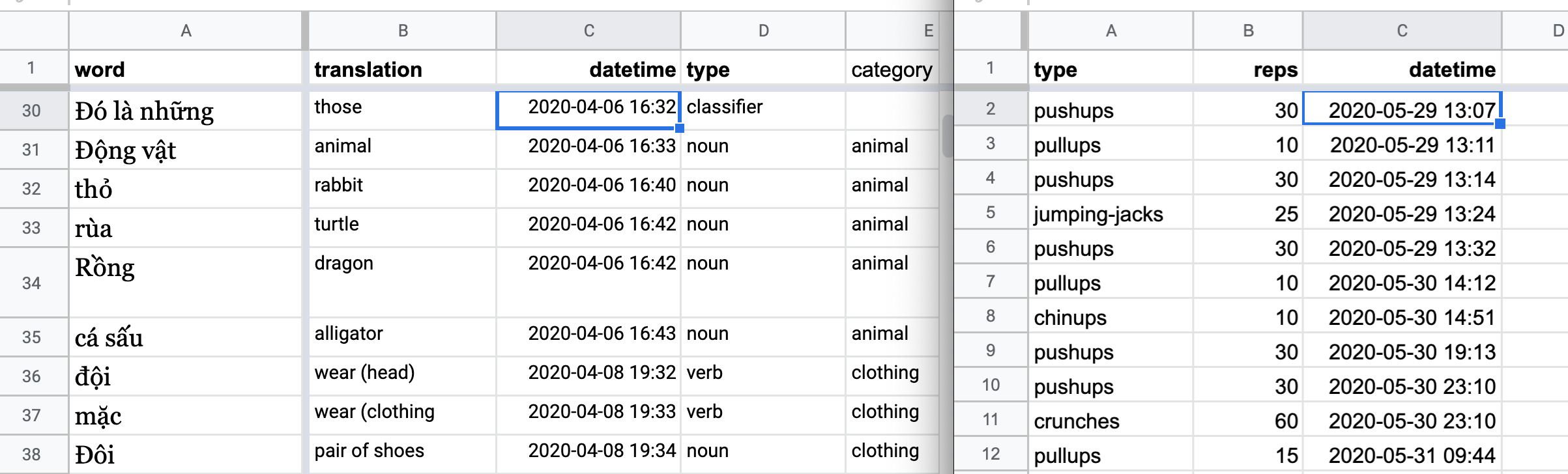

One of my most frequent everyday usecases for spreadsheets is casual tracking of personal activity, like daily exercise, or my progress in Duolingo; here’s what the spreadsheets for those two examples look like, respectively:

You’ll notice that both have a datetime field – I include this not because I’m particularly anal about when exactly I did something, but because maybe down the road I want to do a quickie pivot table analysis, like how often I did things in the morning versus evening, or weekday versus weekend, etc.

More data is generally better than less, since if I don’t capture this info, I can’t go back in time to redo the spreadsheet. However, the mundane work of data entry for an extra field, especially added up over months, risks creating enough friction that I might eventually abandon my “casual tracking”.

Google Sheets does provide handy keyboard shortcuts for adding date and time to a field:

Ctrl/Cmd+:to insert date:7/21/2020Ctrl/Cmd+Shift+:to insert time:3:25:24 PMCtrl/Cmd+Alt+Shift+:to insert the full timestamp:7/21/2020 12:05:46

However, doing that per row is still work; more importantly, I wanted to be able to use the iOS version of Google Sheets to enter exercises as soon as I did them (e.g. random sets of pushups or pullups), and these time/date shortcuts are non-existent.

What I needed was for the datetime field to be automatically be filled each time I started a new row, i.e. as soon as I filled out the first field of a new row, e.g. Duolingo word or exercise type.

The solution

What I wanted can be done by using the Script Editor and writing a Google Apps Script snippet. Here are the steps:

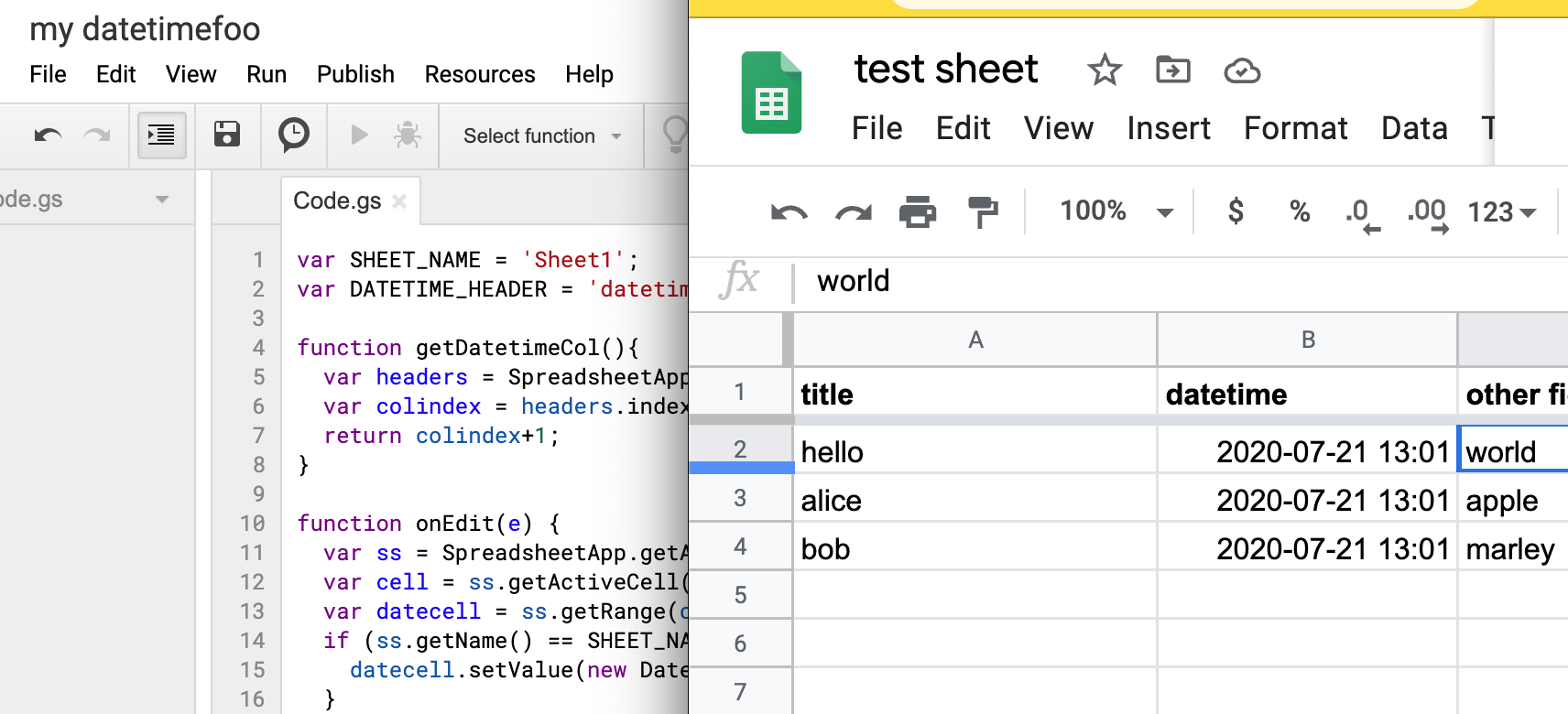

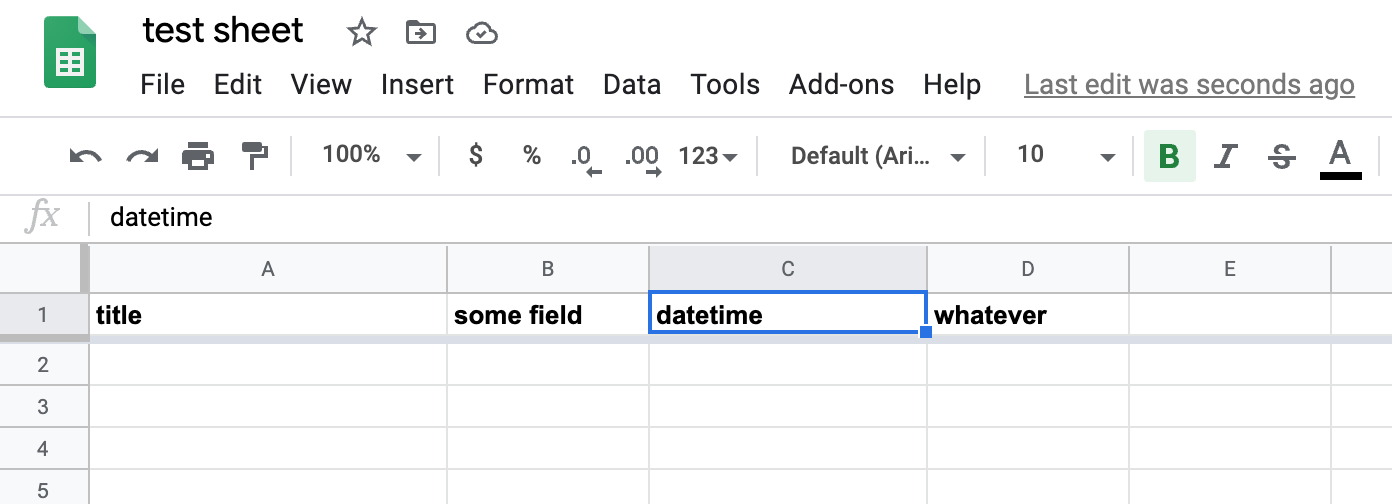

First, create a Google Sheet that has at least 2 columns, and with one of the non-first columns titled datetime:

Then, from the menubar, open Tools » Script Editor:

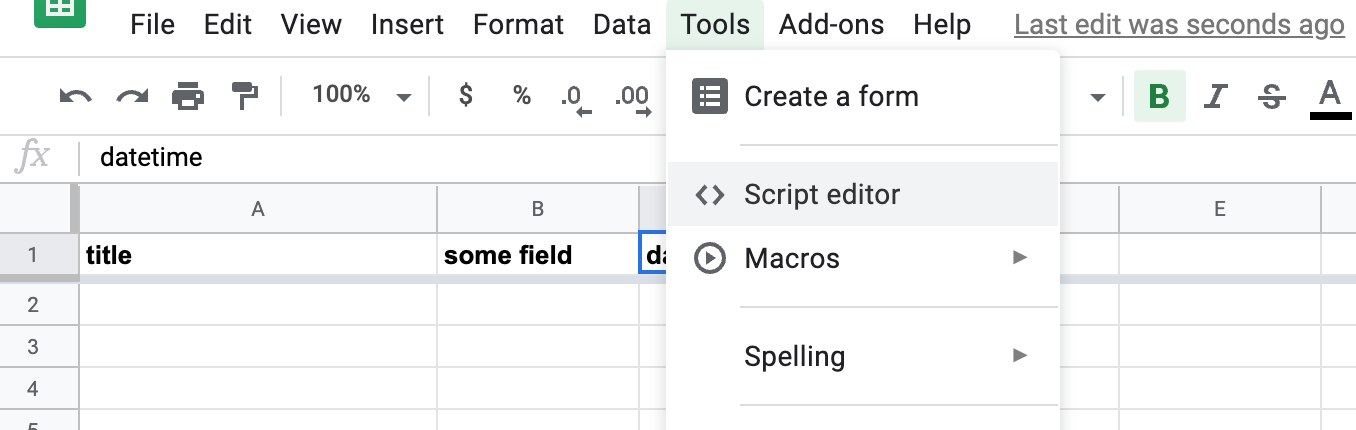

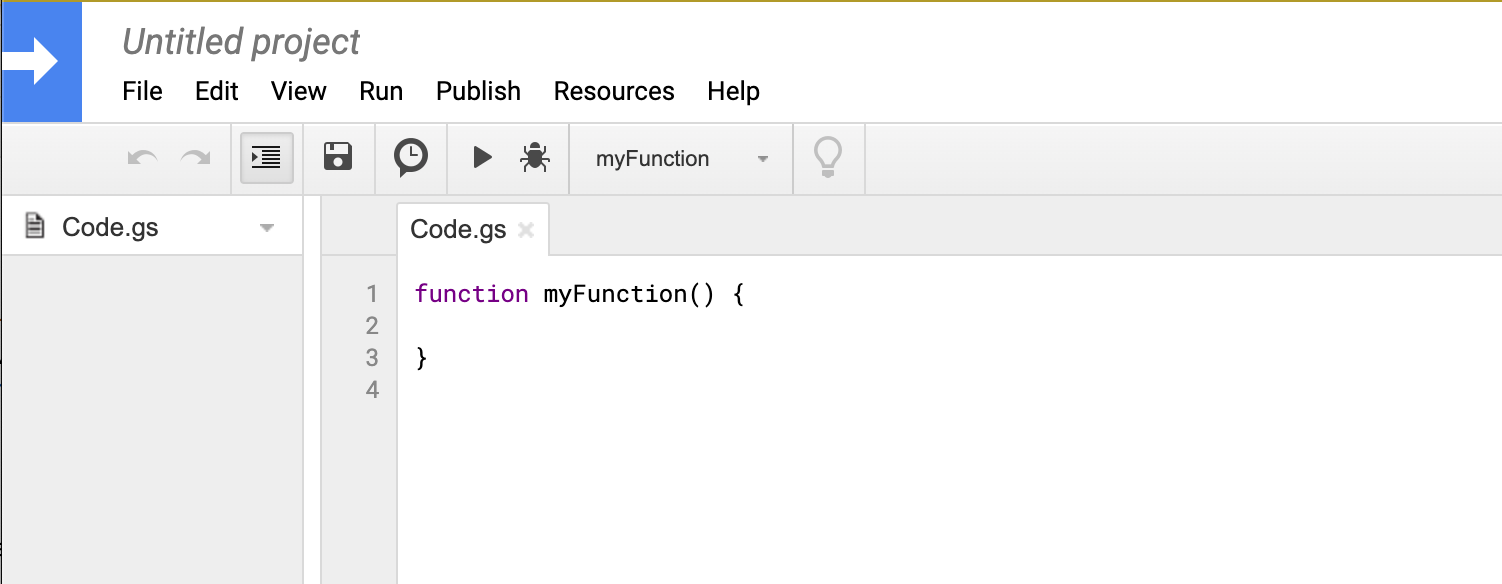

This will take you to a blank template for a new Google App Script project/file:

One of the features of Google Apps Script for Google Sheets is simple triggers, i.e. functions with reserved names like onOpen(e), onEdit(e), and onSelectionChange(e) that execute on common document events. What we want is to change a row (i.e. insert a timestamp) when it is edited, so we want onEdit(e):

function onEdit(e) {

}

But before we get into onEdit, we want a helper function that, given a fieldname like "datetime", it returns the column index as Google Sheets understands it, e.g. 2, in the given screenshot examples. Here’s one way to write that function, which we’ll call getDatetimeCol():

var SHEET_NAME = 'Sheet1';

var DATETIME_HEADER = 'datetime';

function getDatetimeCol(){

var headers = SpreadsheetApp.getActiveSpreadsheet().getSheetByName(SHEET_NAME).getDataRange().getValues().shift();

var colindex = headers.indexOf(DATETIME_HEADER);

return colindex+1;

}

The onEdit() function can be described like this:

- get the currently edited cell (which requires getting the currently active sheet)

- if the edited cell (i.e. active cell) is in the first column

- and it is not blank

- and the corresponding datetime field is blank

- then set the value of the datetime field to the current timestamp – in this example, I use the ISO 8601 standard of

2020-07-20 14:03

Here’s the entire code snippet with both functions:

var SHEET_NAME = 'Sheet1';

var DATETIME_HEADER = 'datetime';

function getDatetimeCol(){

var headers = SpreadsheetApp.getActiveSpreadsheet().getSheetByName(SHEET_NAME).getDataRange().getValues().shift();

var colindex = headers.indexOf(DATETIME_HEADER);

return colindex+1;

}

function onEdit(e) {

var ss = SpreadsheetApp.getActiveSheet();

var cell = ss.getActiveCell();

var datecell = ss.getRange(cell.getRowIndex(), getDatetimeCol());

if (ss.getName() == SHEET_NAME && cell.getColumn() == 1 && !cell.isBlank() && datecell.isBlank()) {

datecell.setValue(new Date()).setNumberFormat("yyyy-MM-dd hh:mm");

}

};

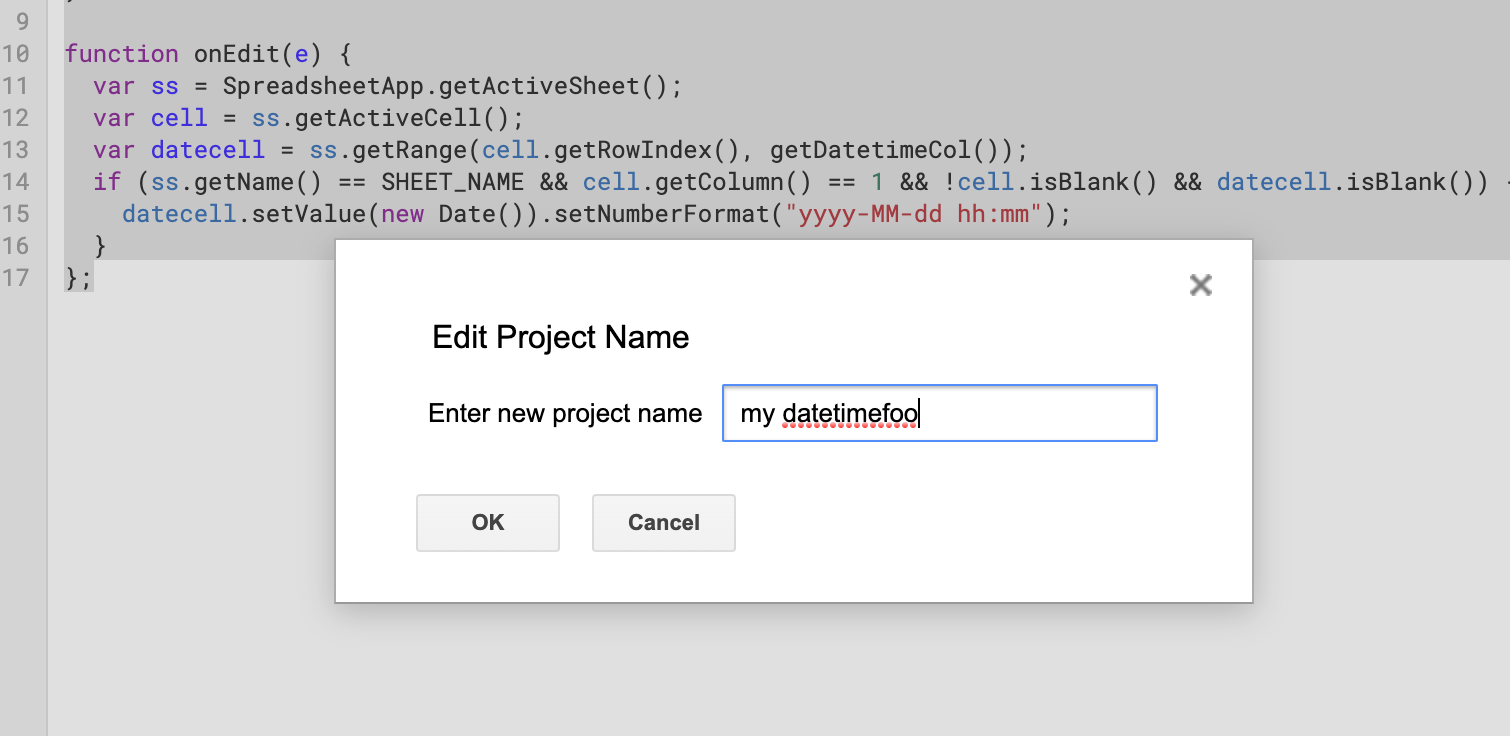

Now, select File » Save and give your project a name (it can be anything):

And your sheet should have the power of auto-inserted timestamps:

Big thanks to the following resources, from which I adapted my solution:

NYPD Stop, Question, and Frisk Worksheet (UF-250); My attempt at getting the latest version as 'just a researcher'

June 26, 2020 update: I hadn’t received a response to this and let it fall by the wayside, but a few people have emailed asking for an update, so I will try again. Note that the Bloomberg era of NYPD Stop and Frisk made the news during his 2020 presidential candidacy.

I’m writing a book about using SQL for data journalism, and one of the sections will be about the NYPD’s Stop and Frisk data, which has a long history as both data and policy. In my book, I frequently assert that researching the data is much more important than any programming and database skill. And this includes finding the actual forms – paper or electronic – used for collecting the data.

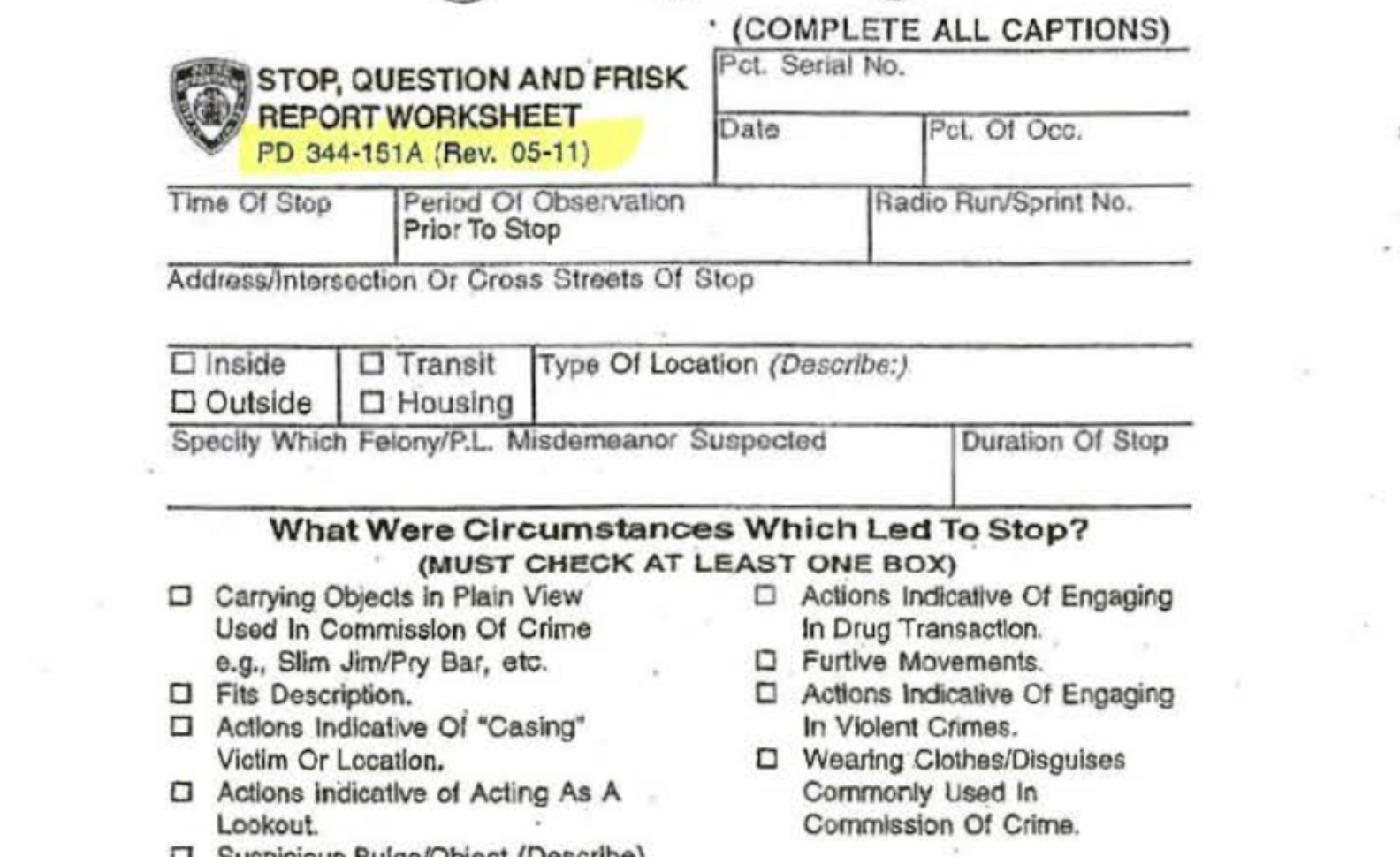

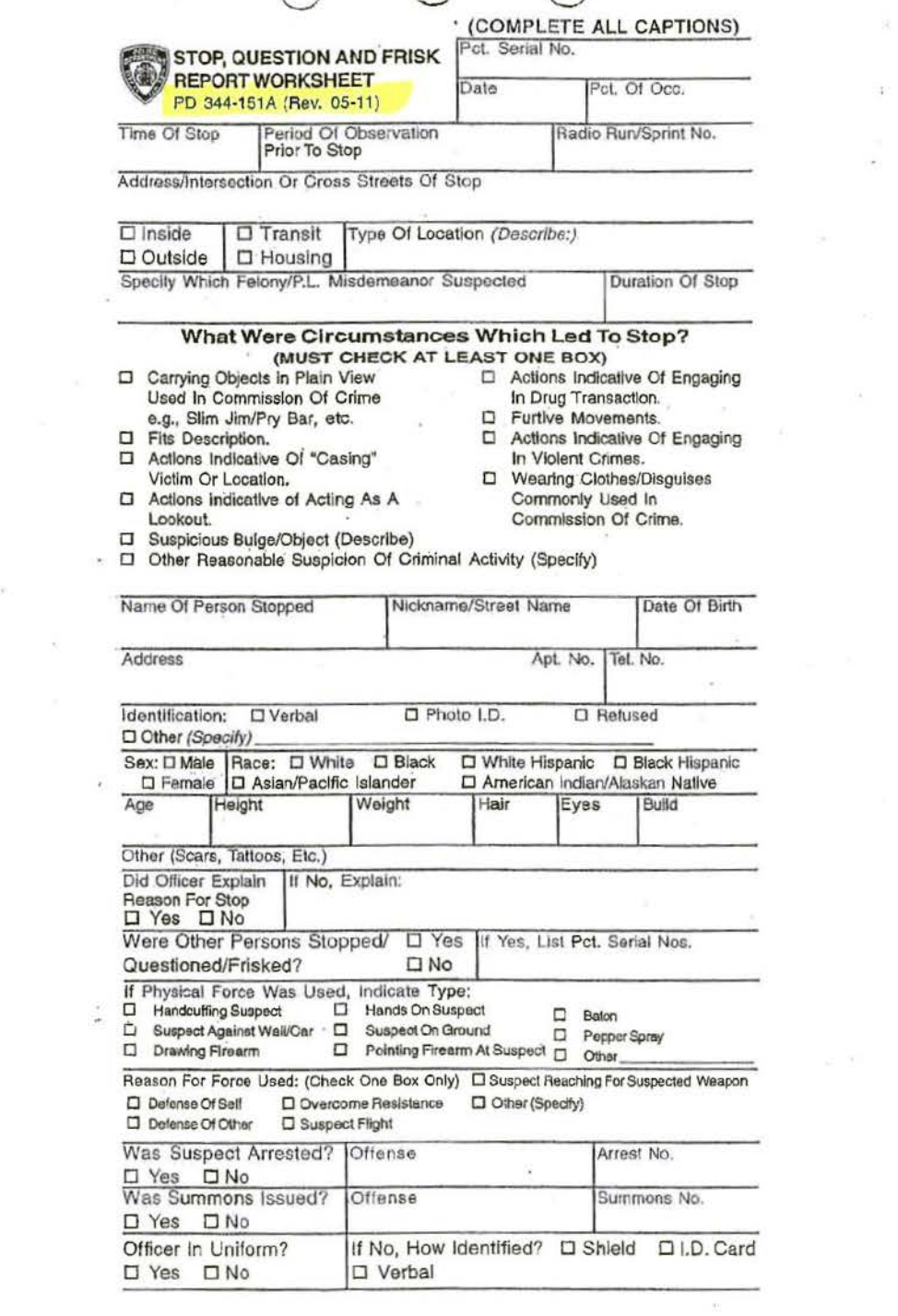

For a stop-and-frisk encounter by the NYPD, police officers have to fill out a Stop, Question, and Frisk Worksheet (PD 344-151A), also known as a Unified Form 250, aka UF-250. The 2011 version has two sides.

This is the first:

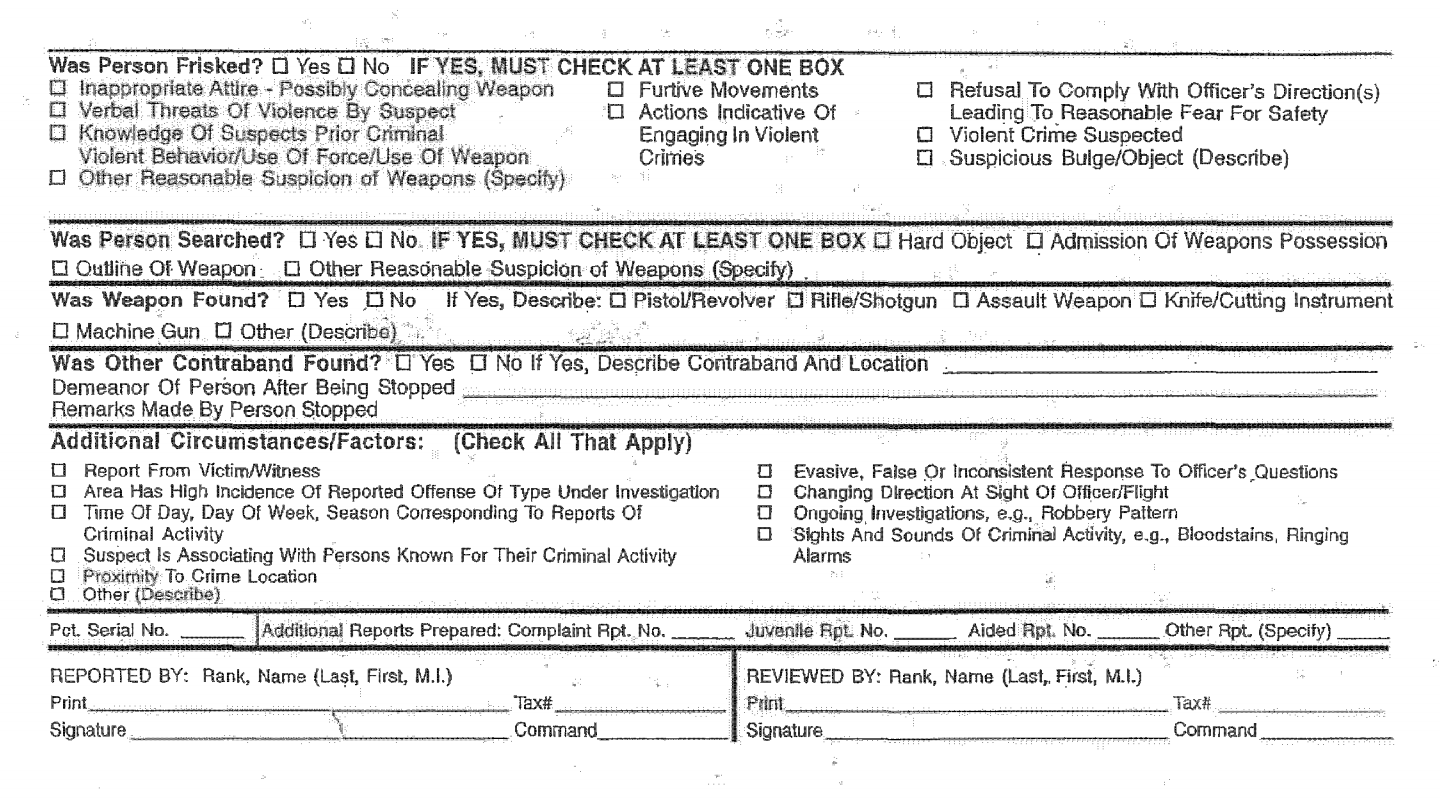

And the second side:

However, after a federal judge ruled in 2013 that the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk practices violated the constitutional rights of New York’s minorities, the NYPD agreed in 2015 to revise the form, which included requiring officers to write a detailed explanation for why they made a stop.

(2) THE DEPARTMENT FORM ENTITLED STOP, QUESTION AND FRISK REPORT WORKSHEET (PD 344-151A), COMMONLY REFERRED TO AS A UF 250 FORM, MUST BE REVISED TO INCLUDE A NARRATIVE SECTION WHERE AN OFFICER MUST RECORD, IN HIS OR HER OWN WORDS, THE BASIS FOR THE STOP. THE NEW FORM MUST ALSO INCLUDE A SEPARATE EXPLANATION OF WHY A FRISK WAS CONDUCTED. THE CHECKBOX SYSTEM CURRENTLY IN USE MUST BE SIMPLIFIED AND IMPROVED.

Previously, NYPD officers could simply check a box labeled with “Furtive Movements”, which was apparently the sole and vague reason for half of the 600,000 stops conducted in 2010, and which led to the lawsuit in the first place.

Anyway, I need this new version of UF-250 for my book. But I could not find it via my Google-fu, including searches for stop frisk site:nyc.gov filetype:pdf and 344-151A filetype:pdf, so I guess it’s time to contact the NYPD’s Public Information office.

It’s just a form, so I wouldn’t think it requires the formality of a FOIL request (right?) and the boilerplate language. So I’ll try a friendly email. For the first time in awhile, I’m making this kind of request as someone not currently working for a journalism organization, so here’s how I worded the email, sent from my personal GMail account:

Hello,

My name is Dan Nguyen and I am researching law enforcement policy. I’ve been able to find past revisions of the UF-250 form used in Stop and Frisks, such as from 2000 [1] and 2007 [2], but I haven’t found any since the 2015 Floyd v. City of New York decision [3], which required these revisions:

… THE DEPARTMENT FORM ENTITLED STOP, QUESTION AND FRISK REPORT WORKSHEET (PD 344-151A), COMMONLY REFERRED TO AS A UF 250 FORM, MUST BE REVISED TO INCLUDE A NARRATIVE SECTION WHERE AN OFFICER MUST RECORD, IN HIS OR HER OWN WORDS, THE BASIS FOR THE STOP. THE NEW FORM MUST ALSO INCLUDE A SEPARATE EXPLANATION OF WHY A FRISK WAS CONDUCTED. THE CHECKBOX SYSTEM CURRENTLY IN USE MUST BE SIMPLIFIED AND IMPROVED.

Could you direct me to where the latest revision of UF-250 exists on the NYPD’s website? Or send to my email (d+++++++++@gmail.com).

Thank you, Dan Nguyen

References:

[1] https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/ccrb/downloads/pdf/policy_pdf/issue_based/20010601_sqf.pdf

[2] https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/public_information/TR534_FINALCompiled.pdf

Note: So I sent this email before I blogged about it, which is why there this error in the text: the Floyd v. City of New York decision was in 2013; 2015 is the date of the NYPD memo asserting the new revisions. Oops.

As for why I’m blogging this: just for funsies. If I get a response, I’ll update and link to the new form for the benefit of fewer researchers. And if not, I’ll update and append my ongoing FOIL adventure.

Other useful reading and links (updated June 2020):

- CourtListener/PACER: Davis v. The City of New York (1:10-cv-00699) Docket

- MEMO ENDORSEMENT on re: (246 in 1:12-cv-02274-AT-HBP) Status Report filed by Peter L Zimroth, (354 in 1:10-cv-00699-AT-HBP) Status Report filed by Peter L. Zimroth, (526 in 1:08-cv-01034-AT-HBP) Status Report filed by Peter A. Zimroth, re: Recommendation Regarding Stop Report Form. ENDORSEMENT: APPROVED. SO ORDERED. (Signed by Judge Analisa Torres on 3/25/2016) (kko) (Entered: 03/25/2016)

- NYCLU March 2019 Report: Stop-and-Frisk in the de Blasio Era

- NY Daily News: NYPD stop-and-frisk numbers jumped by 22% in 2019 from prior year: report

- Gothamist: NYC Has “A Long Way To Go” To End The Illegal Stop-And-Frisk Era

-

NYT: The Lasting Effects of Stop-and-Frisk in Bloomberg’s New York

- NYPD Patrol Guide: Procedure No. 212-11: INVESTIGATIVE ENCOUNTERS: REQUESTS FOR INFORMATION, COMMON LAW RIGHT OF INQUIRY AND LEVEL 3 STOPS

- NYPD Patrol Guide: Procedure No. 221-02: USE OF FORCE

- Chicago Police Investigatory Stop Report

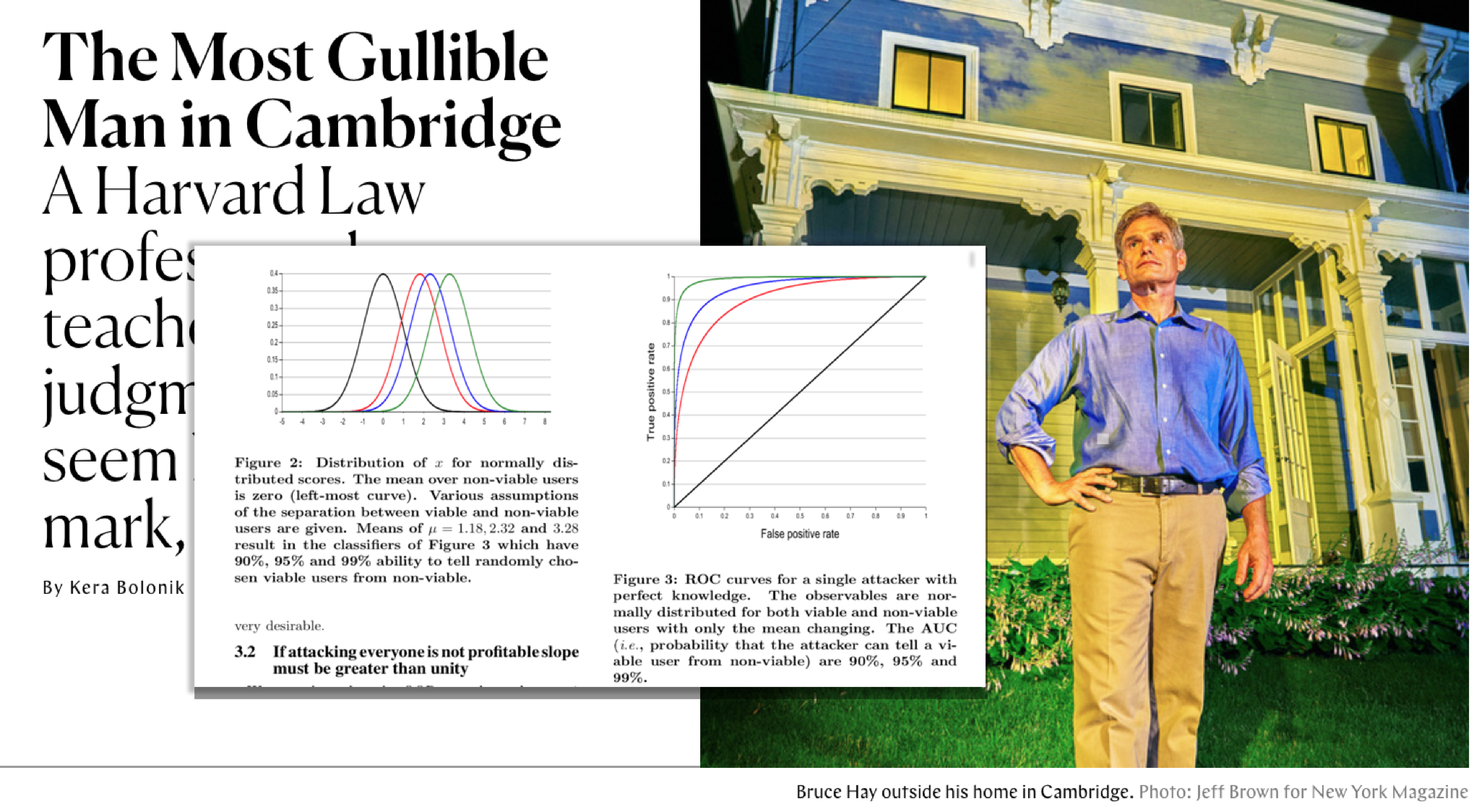

The scammers of Harvard Law's Bruce Hay and the "Nigerian Prince" filter

There’s too much to process in “The Most Gullible Man in Cambridge “, the Kera Bolonik longform piece that dropped yesterday on the New York Magazine/The Cut website. For starters, just how completely bananas it is from top to bottom. And then, whether the main character and victim, Professor Bruce Hay of Harvard Law, is a reliable and trustworthy narrator. And of course, the absolute marvel of long suffering patience and wisdom that is his ex-wife (more on that later) and mother of his young children.

Because of its many bizarre elements and threads, Bolonik’s article feels much longer than its 7,000-word count and is hard to summarize. But to do it in one convoluted sentence: Professor Hay is the victim of an alleged paternity scam, one so elaborate it nearly cost him and his family their home, and one that includes sexual misconduct allegations leading to an ongoing Title IX investigation.

The story’s most notable feature is just how gullible and how dumb Professor Hay – who is the on-record source of 90-95% of the narrative – makes himself sound. In this case, a sentence (or several) can’t do Bolonik’s article justice. But one particularly interesting aspect is how seemingly obvious the ploy seems to be, and yet, how it managed to fool several highly intelligent men, including Professor Hay and – as far as we know – three Harvard-area men.

From the story’s first graf, this is how Hay describes his first encounter with the scammer; I’ve added emphasis to the pickup line:

It was just supposed to have been a quick Saturday-morning errand to buy picture hooks. On March 7, 2015, Harvard Law professor Bruce Hay, then 52, was in Tags Hardware in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near his home, when a young woman with long reddish-brown hair approached him to ask where she could find batteries. It was still very much winter, and, once the woman got his attention, he saw that underneath her dark woolen coat and perfectly tied scarf she was wearing a dress and a chic pair of boots — hardly typical weekend-errand attire in the New England college town. When he directed her to another part of the store, she changed the subject. “By the way, you’re very attractive,” he remembers her saying.

In the latter-third of the story, Bolonik writes that Hay and his lawyer uncovered 3 other men who previously filed suit against his scammer. Bolonik met with one of them, who is referred to in court papers as “John Doe”. Here’s how Doe describes meeting the scammer (again, emphasis mine)

This past fall, I met Doe, who told me Shuman appeared out of nowhere at an intersection where he was standing with two colleagues and started chatting him up in what he described as hushed tones. He recalled her saying, “Excuse me, but I couldn’t help but notice that you’re attractive. I’m in town from New York, visiting a friend, and I was hoping you’d be willing to show me around.” He gave her his cell number.

Everything is obvious in retrospect, but here the pickup line, and its contrived circumstances – how many late-20s/early-30s adults show up in Boston or New York without a smartphone to serve as a guide? – seem especially so. How could Doe, described by Bolonik as a “young, lanky, blue-eyed CPA”, or Hay, a tenured professor with nearly 30 years at Harvard Law, fall for something so comically transparent?

Those questions about the depths of human trust and gullibility aren’t readily answered. But I do wonder if the flimsiness of the pickup tactic itself is itself inspired by the trope of the Nigerian Prince email scam, an ostensibly obvious and universally-known scam, yet one that still brings in fortunes for its perpetrators?.

But couldn’t scammers attract even more victims and their money by being more sophisticated? e.g. pretending to be a prince from a country less notorious than Nigeria? In 2012, Microsoft Research’s Cormac Herley studied this question in one of my favorite white papers, Why Do Nigerian Scammers Say They are From Nigeria? (link to PDF).

Here’s an excerpt from the Discussion section (Section 4):

An examination of a web-site that catalogs scam emails shows that 51% mention Nigeria as the source of funds…Why so little imagination? Why don’t Nigerian scammers claim to be from Turkey, or Portugal or Switzerland or New Jersey? Stupidity is an unsatisfactory answer.

It’s a very accessible paper and worth reading, but in summary, Herley argues that the use of “Nigeria” (or “Nigerian Prince”) acts as a very effective filter for the scammer, whose has nearly unlimited bandwidth in the amount of emails sent, but very limited time to deal with “false positives” – i.e. potential victims who ultimately wise up. The percentage of targets who would even open an unsolicited email subject line of “Nigeria” is vanishingly and staggeringly tiny. But the ones who do, Herley argues, are extremely profitable to the scammer:

If we assume that the scammer enters into email conversation (i.e., attacks) almost everyone who responds, his main opportunity to separate viable from non-viable users is the wording of the original email…Who are the most likely targets for a Nigerian scammer? Since the scam is entirely one of manipulation he would like to attack (i.e., enter into correspondence with) only those who are most gullible…

Since gullibility is unobservable, the best strategy is to get those who possess this quality to self-identify. An email with tales of fabulous amounts of money and West African corruption will strike all but the most gullible as bizarre. It will be recognized and ignored by anyone who has been using the Internet long enough to have seen it several times.

It will be figured out by anyone savvy enough to use a search engine and follow up on the auto-complete suggestions such as shown in Figure 8. It won’t be pursued by anyone who consults sensible family or friends, or who reads any of the advice banks and money transfer agencies make available. Those who remain are the scammers ideal targets. They represent a tiny subset of the overall population.

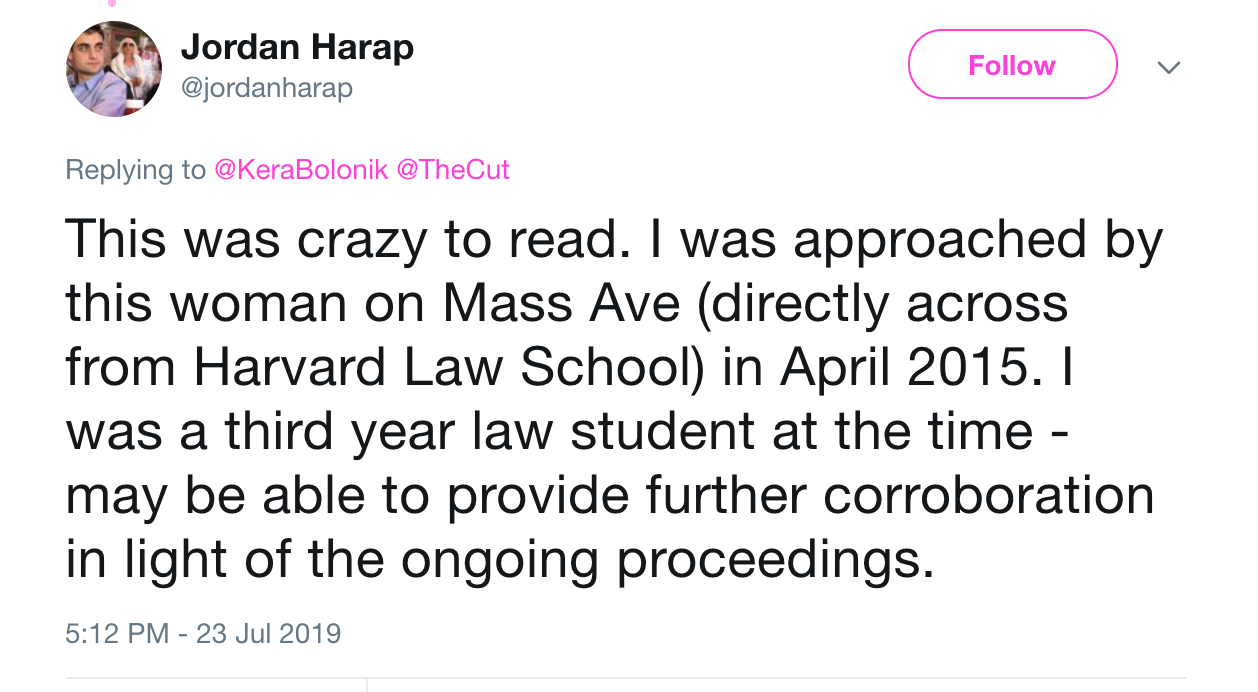

Reading through the Twitter replies to NYMag’s Bolonik, there’s at least one more guy who has a story about the scammer – though apparently, he appears to have avoided the trap:

Hay’s alleged scammer seems to have some of the same constraints as a Nigerian scammer – it’s a huge amount of time and risk to initiate a relationship with a mark who is likely to wise up. So the exceedingly cringe pickup line of “Excuse me, sir, I’mbut I noticed you’re very handsome. Could you show me around New York?” likely had any rejections before finding success in Professor Hay, “John Doe”, and other victims. And this works beautifully for the paternity-test-scammer.

(Note: Except for this aside, I’ve deliberately avoid mentioning or speculating about the motives of Hay’s scammers, which would require an entirely separate wordy blog post. Bolonik’s article offers little revelation. But it’s worth noting that in Hay’s case, unlike with Nigerian scammers, the scammers don’t seem to be primarily motivated by money)

But as with everything else in Bolonik’s necessarily convoluted article, there are only more questions. Herley, the Microsoft researcher, points out that Nigerian scammers depend on victims lacking a support network of “sensible family or friends”. Professor Hay does not seem to be in this situation; he says he and his scammer, before they first had sex, had coffee dates and long talks about their respective lives. She would have learned from him that his ex-wife – who he has 2 children with and who he was still living with, amicably – is an assistant U.S. Attorney. At that point, the ostensibly savvy scammer must have realized that no matter how gullible Hay seemed, or how estranged he might be from the rest of Harvard’s elite, Hay’s ex-wife was definitely going to step in and pursue any scammers who threatened Hay’s (i.e. her) home and children.

And yet here we are. The depths and speed at which Professor Hay fell for the scam is shocking. But it doesn’t explain why (again, assuming that money is not an issue) the scammers would entangle themselves with him, when there are so many other marks. This incongruity (among the many others), added to the fact Hay – against the advice of Harvard and other lawyers – shopped his story around to several other journalists before finding Bolonik, is enough to raise serious doubt that we’ve heard all the relevant and significant facts of this bizarre story.

How to install and use schemacrawler on MacOS to generate nifty SQL database schemas

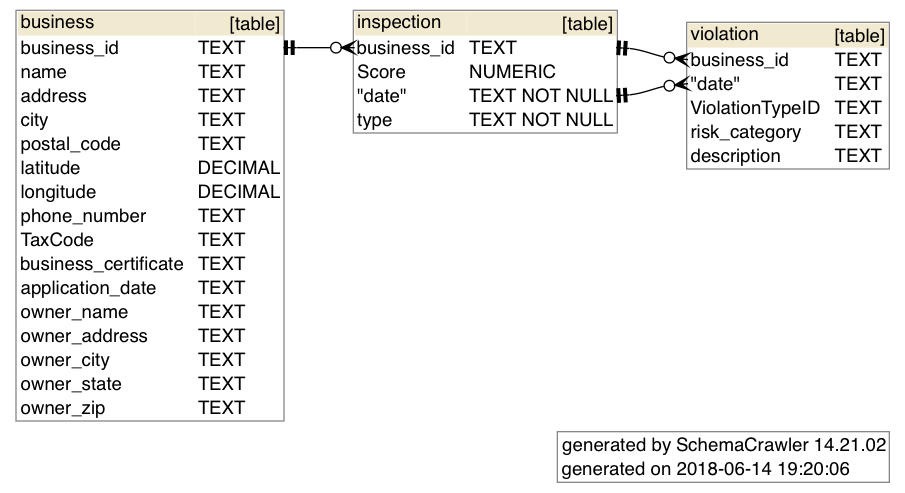

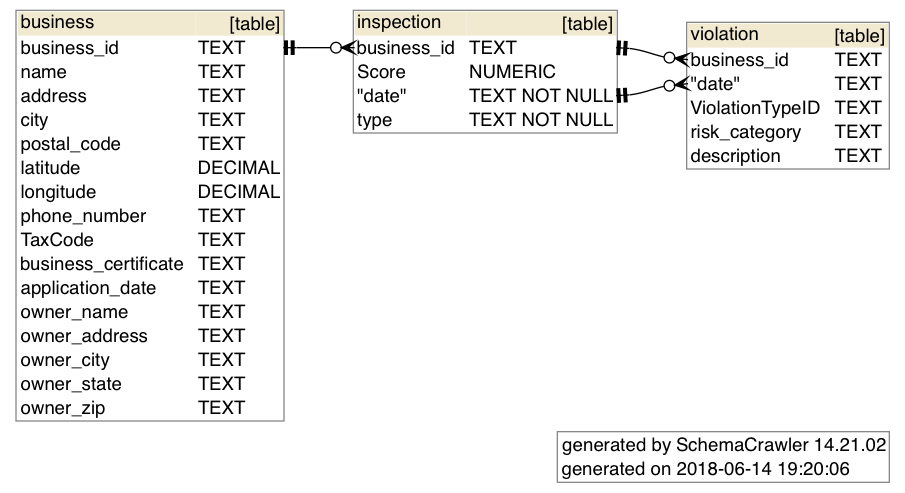

The following post is a copy of this Gist, an instruction recipe I wrote on how to get the superhandy schemacrawler program working on MacOS. It’s a command-line tool that allows you to easily generate SQL schemas as image files, like so:

This was tested on MacOS 10.14.5 on 2019-07-16

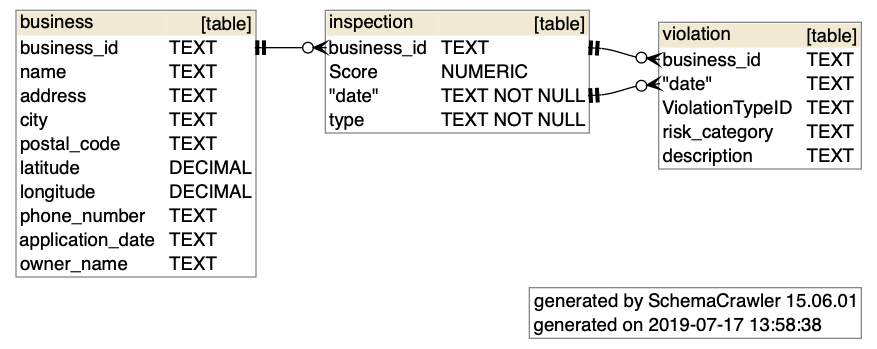

schemacrawler is a free and open-source database schema discovery and comprehension tool. It can be invoked from the command-line to produce, using GraphViz, images/pdfs from a SQLite (or other database type) file. It can be used from the command-line to generate schema diagrams like these:

To see more examples of commands and diagrams, visit scheacrawler’s docs: http://www.schemacrawler.com/diagramming.html

Install graphviz dependency

For schema drawing, schemacrawler uses graphviz, which can be installed via the Homebrew package manager:

brew install graphviz

Installing schemacrawler as a command-line tool

This section gives an example of how to install schemacrawler so that you can invoke it with your shell. There isn’t a Homebrew recipe, so the shell commands basically:

- Download a release zip from schemacrawler/releases

- Copies the relevant subdir from the release into a local directory, e.g.

/usr/local/opt/schemacrawler - Creates a simple shell script that saves you from having to run

schemacrawlervia thejavaexecutable - symlinks this shell script into an executable path, e.g.

/usr/local/bin

Downloading and installing schemacrawler

The latest releases can be found on the Github page:

https://github.com/schemacrawler/SchemaCrawler/releases/

Setting up schemacrawler to run on your system via $ schemacrawler

In this gist, I’ve attached a shell script script-schemacrawler-on-macos.sh that automates the downloading of the schemacrawler ZIP file from its Github repo, installs it, creates a helper script, and creates a symlink to that helper script so you can invoke it via:

$ schemacrawler ...

You can copy the script into a file and invoke it, or copy-paste it directly into Bash. Obviously, as with anything you copy-paste, read it for yourself to make sure I’m not attempting to do something malicious.

(An older version of this script can be found here)

A couple of notes about

The script script-schemacrawler-on-macos.sh has a few defaults – e.g. /usr/local/opt/ and /usr/local/bin/ – which are assumed to be writeable, but you can change those default vars for yourself.

One of the effects of is that it creates a Bash script named something like

Its contents are:

This script is a derivation of schemacrawler’s schemacrawler-distrib/src/assembly/schemacrawler.sh, the contents of which are:

General usage

Now that schemacrawler is installed as an executable shell command, here’s an example of how to invoke it – change DBNAME.sqlite and OUTPUT_IMAGE_FILE.png to something appropriate for your usecase:

schemacrawler -server sqlite \

-database DBNAME.sqlite \

-user -password \

-infolevel standard \

-command schema \

-outputformat png \

-outputfile OUTPUT_IMAGE_FILE.png

Bootload a sample SQLite database and test out schemacrawler

Just in case you don’t have a database to play around with, you can copy paste this sequence of SQLite commands into your Bash shell, which will create the following empty database file at /tmp/tmpdb.sqlite

echo '''

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS business;

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS inspection;

DROP TABLE IF EXISTS violation;

CREATE TABLE business (

business_id TEXT,

name TEXT,

address TEXT,

city TEXT,

postal_code TEXT,

latitude DECIMAL,

longitude DECIMAL,

phone_number TEXT,

application_date TEXT,

owner_name TEXT

);

CREATE TABLE inspection (

business_id TEXT,

"Score" NUMERIC,

date TEXT NOT NULL,

type TEXT NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY(business_id) REFERENCES business(business_id)

);

CREATE TABLE violation (

business_id TEXT,

date TEXT,

"ViolationTypeID" TEXT,

risk_category TEXT,

description TEXT,

FOREIGN KEY(business_id, date) REFERENCES inspection(business_id, date)

);''' \

| sqlite3 /tmp/tmpdb.sqlite

Invoke schemacrawler like so:

schemacrawler -server sqlite \

-user -password \

-infolevel standard \

-command schema \

-outputformat png \

-database /tmp/tmpdb.sqlite \

-outputfile /tmp/mytmpdb.png

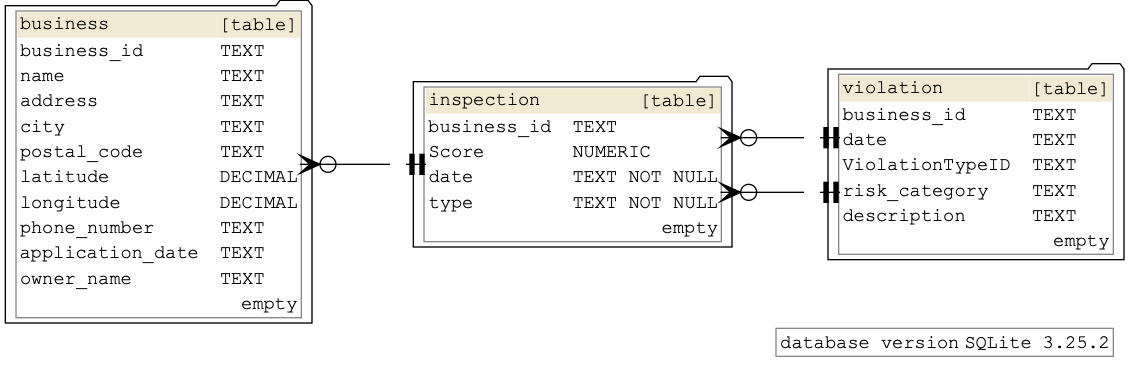

The output of that Bash command will be a file /tmp/tmpdb.sqlite, which looks like this:

graphviz properties

You can edit schemacrawler.config.properties, which is found wherever you installed the schemacrawler distribution – e.g. if you ran my installer script, it would be in /usr/local/opt/schemacrawler/config/schemacrawler.config.properties

Some example settings:

schemacrawler.format.no_schemacrawler_info=true

schemacrawler.format.show_database_info=true

schemacrawler.format.show_row_counts=true

schemacrawler.format.identifier_quoting_strategy=quote_if_special_characters

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.nodes.ranksep=circo

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.graph.layout=circo

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.graph.splines=ortho

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.node.shape=folder

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.node.style=rounded,filled

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.node.fillcolor=#fcfdfc

#schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.node.color=red

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.graph.fontname=Helvetica Neue

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.node.fontname=Consolas

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.edge.fontname=Consolas

schemacrawler.graph.graphviz.edge.arrowsize=1.5

If you append the previous snippet to the default schemacrawler.config.properties, you’ll get output that looks like this:

More info about GraphViz in this StackOverflow Q:

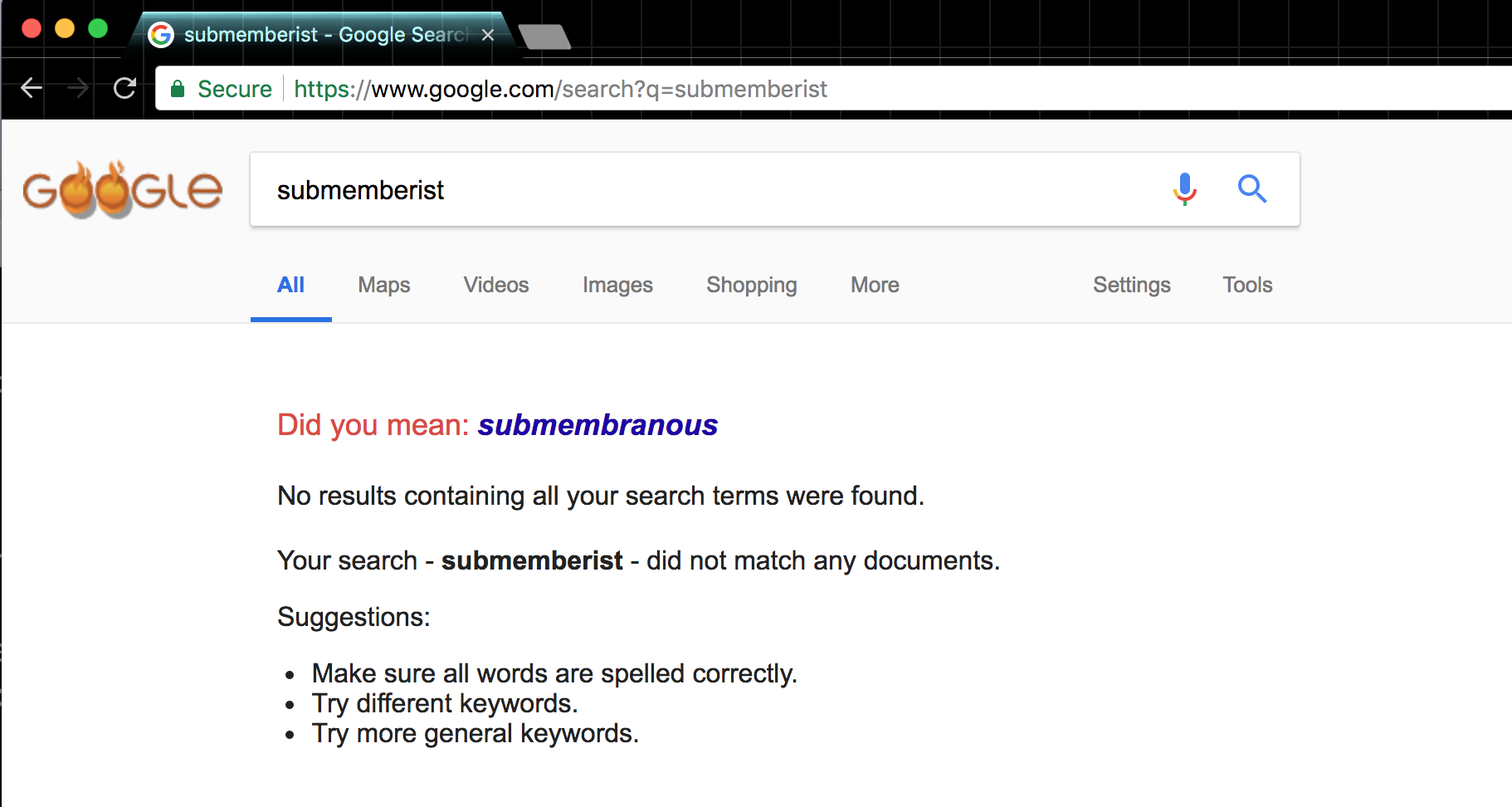

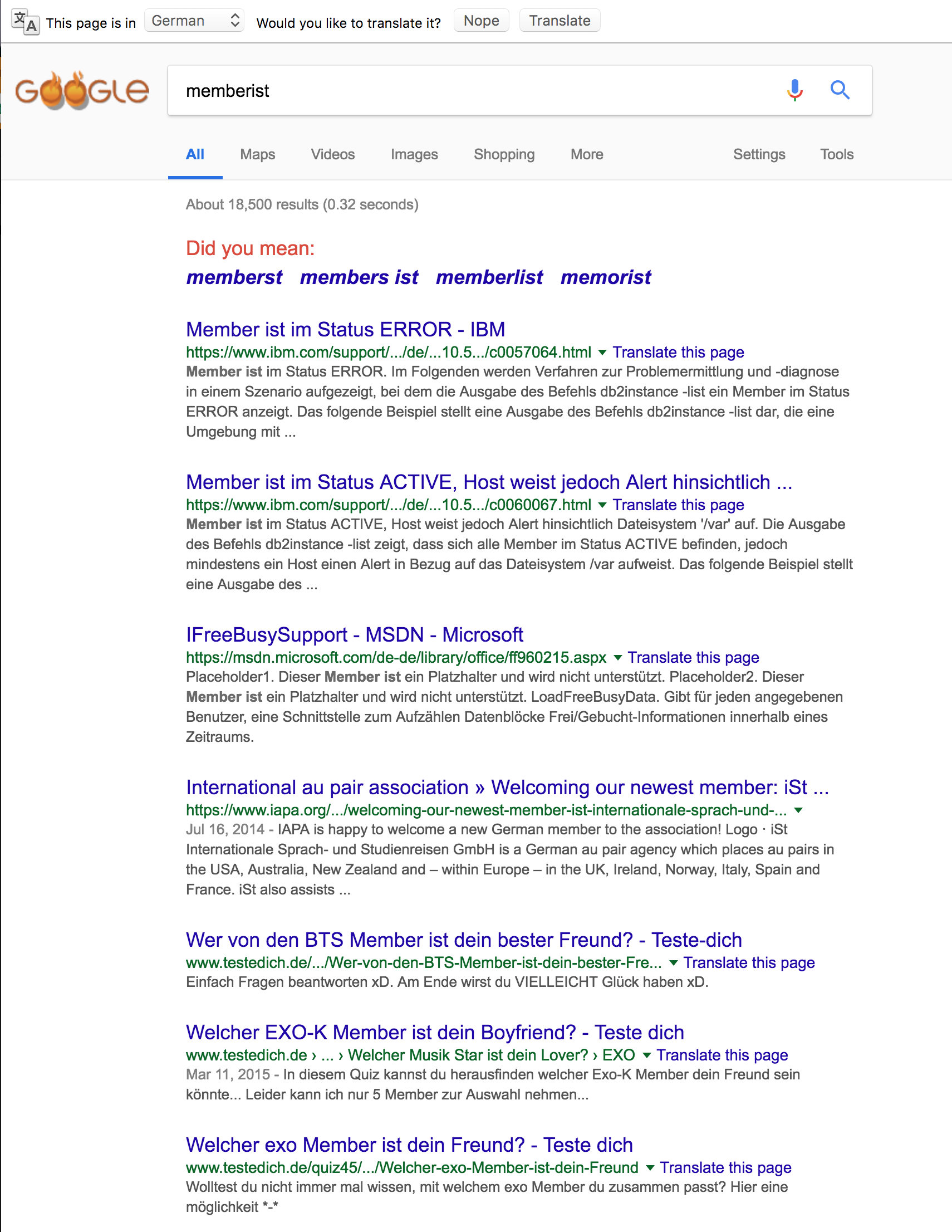

A submemberist?

It’s a given that Google has pages for every valid English word in existence as well as most fantastical words. It’s very rare that Google comes up with nothing, even for nonsense or terribly misspelled words.

However, I stumbled upon a non-result for the word “submemberist”:

https://www.google.com/search?q=submemberist

Of course, by the time you click on the above query, Google will have crawled at least a few pages mentioning the word.

I guess it’s probably not a big deal to come up with arbitrary combinations of letters for which Google has no results. What was interesting about “submemberist” is that it looks like it could be a word. Though to be fair, the Oxford “Living” Dictionary only has it listed with a hyphen: “sub-member”.

I didn’t even know “submember” or “sub-member” was a word before I saw Parker Higgins (@xor) tweet some fun trivia about airport codes last night:

As far as I can tell, the longest words you can spell entirely out of airport codes are each 9 letters long. It's quite an evocative list of words, too. pic.twitter.com/ssNMRz3s5O

— Parker Higgins (@xor) March 28, 2018

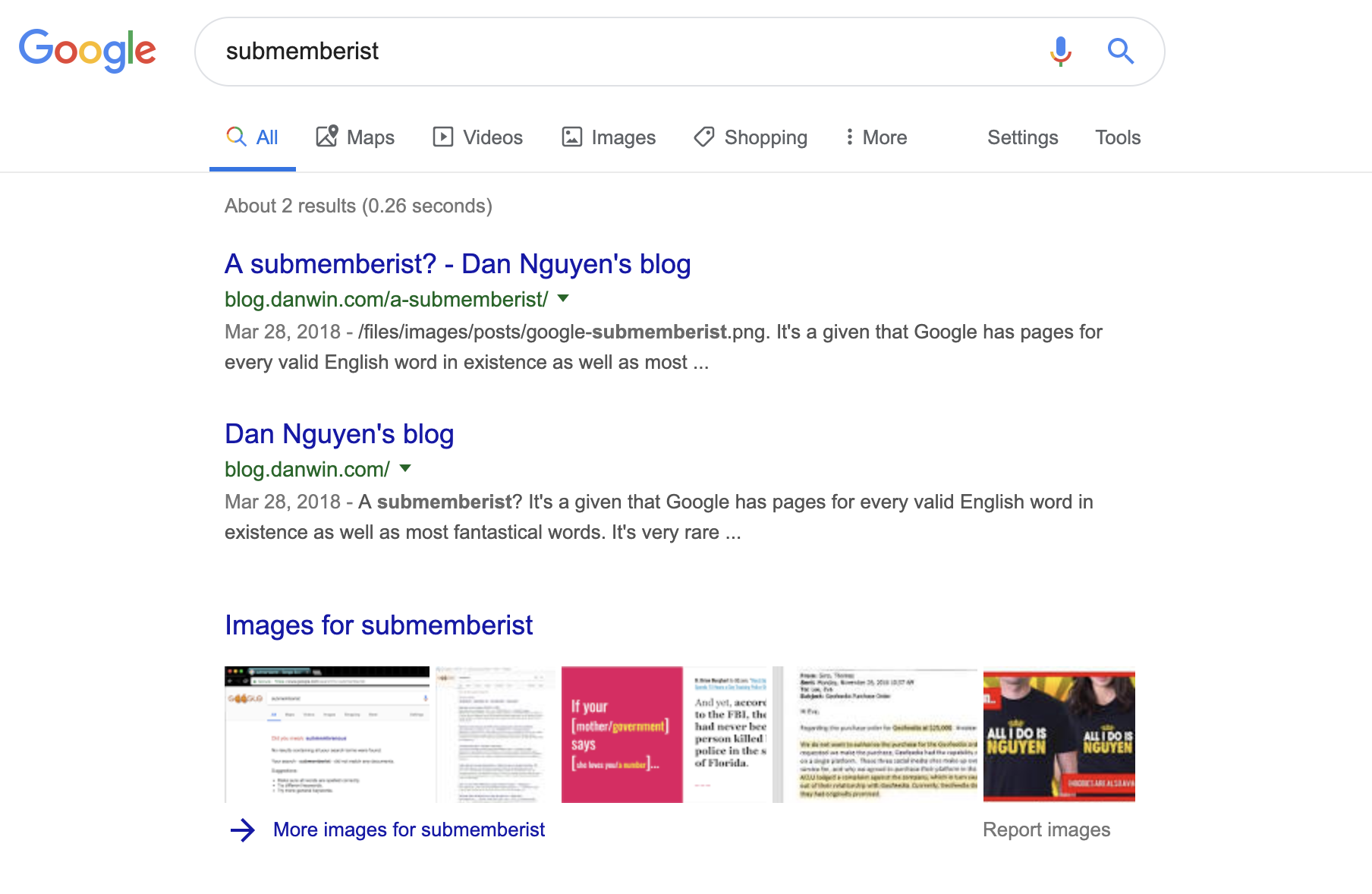

Of all the 3-character codes, “IST” seems the most flexible when it comes to creating a legit combination with a 9-character word. Of course, “memberist” isn’t a word either, though Google at least has plenty of attempted results:

I wish I could say this blog post had a more important point about language or even search-engine optimization, but I just wanted to spoil the results for anyone else who ever searches for “submemberist” :p.

Update 2019-07-16: More than a year later, this blog is the only result for a google search of “submemberist”, which means my blog apparently isn’t notable enough to get content-scraped by SEO-spammers!

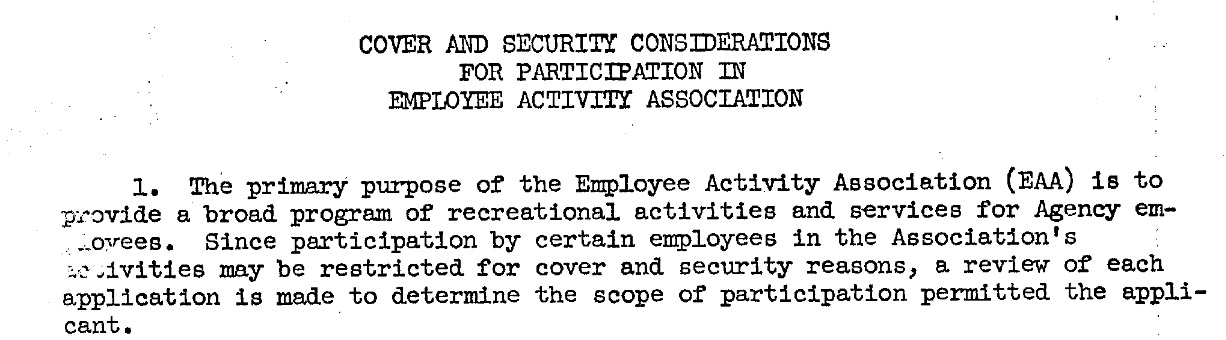

How James Bamford exposed the NSA using the NSA's own company newsletter

MuckRock recently posted a fun FOIA-related item about a declassified CIA memo on “Cover and Security Considerations” for employees who want to have an after-work bowling league or glee club:

In most professions, all it takes to form an after-work bowling league is an overly long email chain and some beer money. As a declassified memo recently unearthed in CREST shows, in the CIA, it’s a lot more complicated.

…To cope with these rather unique challenges, the Agency formed the Employee Activity Association (EAA), which, in exchange for membership dues, would ensure that next weekend’s fishing trip would have a plausible cover story.

…members were expected to keep the existence or non-existence of the ping-pong team a secret and to attend security briefings.

This bureaucratic anal-retentiveness regarding mundane company functions immediately reminded me of James Bamford, the first journalist to bring mainstream attention to the National Security Agency when he published “The Puzzle Palace” in 1982.

There is a great profile of Bamford in Baltimore’s City Paper in which he describes finding an internal NSA newsletter that contained chatty and useful details about the agency and, like your typical chatty company newsletter, was meant for employees and their families. And since family members didn’t have special security clearances, that meant that all the NSA internal newsletters were eligible to be released by FOIA. Bamford was able to get thousands of pages of newsletters about the NSA, and that allowed him to greatly expand his knowledge and access to NSA officials.

Unfortunately, City Paper seems to have undertaken one of those news site redesigns/content-management system overhauls in which the archives are eradicated from Internet history. Luckily, the Internet Archive still has a copy of the original 2008 article by Lee Gardner: Secrets and Lies: An Interview With National Security Agency Expert James Bamford

Here’s the key excerpt, though the entire interview is a great read:

[City Pages]: Did you get any push-back from the agency when you started writing about it? After all, it’s supposed to be top secret.

[Bamford]: I had a difficult time. My advance was fairly small, I was living in Massachusetts, I didn’t really know anyone in intelligence, and I hadn’t written anything before. And I was going up against NSA.

One of the things I was good at in law school was research, so I thought maybe I’d try using the Freedom of Information Act. The problem with that was, NSA is really the only agency excluded from the act. If you sent them a [FOIA] request, they would just send you a letter back saying [under Section 6 of the National Security Agency Act] we don’t have to give you anything, even if it’s unclassified.

But I found this place, the George C. Marshall Research Library in Lexington, Virginia, and William F. Friedman, one of the founders of the NSA, had left all his papers there. When I got down there, I found the NSA had gotten there just before me and gone through all of his papers and taken a lot of his papers out and put them in a vault down there and ordered the archivist to keep them under lock and key. And I convinced the archivist that that wasn’t what Friedman wanted, and he took the documents out and let me take a look at them.

Among the documents was an NSA newsletter. These are things the NSA puts out once a month. They’re fairly chatty, but if you read them closely enough you can pick up some pretty good information about the agency. . . . When I was reading one of the newsletters, there was a paragraph that said, “The contents of this newsletter must be kept within the small circle of NSA employees and their families.” And I thought about it for a little bit, and I thought, hmm, they just waived their protections on that newsletter–if that’s on every single newsletter then I’ve got a pretty good case against them. If you’re going to open it up to family members, with no clearance, who don’t work for the agency, then I have every right to it. That was a long battle, but I won it, and they gave me over 5,000 pages’ worth of NSA newsletters going back to the very beginning. That was the first time anyone ever got a lot of information out of NSA.

We made this agreement where I could come down and spend a week at NSA, and they gave me a little room where I could go over the newsletters and pick the ones I wanted. So I got all that information, and spent about a week at NSA. And finally they really wanted to delete some names and faces, and I said you can do that, but there ought to be some kind of quid pro quo. The quid pro quo was that I get to interview senior officials and take a tour of the agency. And that was what really opened it up.

It wasn’t the NSA you see today–it was much different. They just thought no one would ever try to write about NSA, and they didn’t think I would have any luck, because who am I? I’m just some guy up in Massachusetts with no track record.

Rabbit holes and writing.

It’s about 1:50 A.M. and I’m reading a HN thread about a BBC article, titled “Rabbit hole leads to 700-year-old Knights Templar cave”.

Several users point out that the title is a bit of nonsense – “The reference to a rabbit hole makes no sense unless it’s symbolic, since rabbits holes are about the size of a rabbit”. That gets me thinking about the rabbit holes that led into the seemingly huge warrens described in “Watership Down”.

Googling, “watership down rabbit facts” led me to this 2015 Guardian interview with author Richard Adams; I knew the book originated from a whimsical story Adams made up to keep his daughters entertained on a car trip. I didn’t realize that he had never written fiction before, or that he was so late in his life when he started:

Watership Down was one of the first of these stories. Adams was 52 and working for the civil service when his daughters began pleading with him to tell them a story on the drive to school. “I had been put on the spot and I started off, ‘Once there were two rabbits called Hazel and Fiver.’ And I just took it on from there.” Extraordinarily, he had never written a word of fiction before, but once he’d seen the story through to the end, his daughters said it was “too good to waste, Daddy, you ought to write that down”.

He began writing in the evenings, and the result, an exquisitely written story about a group of young rabbits escaping from their doomed warren, won him both the Carnegie medal and the Guardian children’s prize. “It was rather difficult to start with,” he says. “I was 52 when I discovered I could write. I wish I’d known a bit earlier. I never thought of myself as a writer until I became one.”

On automated journalism: Don't automate the good stuff

I love and frequently recommend Al Weigart’s, “Automate the Boring Stuff with Python”, because it so perfectly captures how I feel about programming: programming is how we tell computers what to do. And computers, like all of the best mechanical inventions in existence, are best at doing mechanical, i.e. boring work.

The inverse of that mentality – that computers should/can be used to automate the interesting work of our lives – can be found in this blog post (h/t @ndiakopoulos) from the research blog Immersive Automation:

[Can computers quote like human journalists, and should they?](http://immersiveautomation.com/2017/03/can-computers-quote-like-human-journalists/)

(emphasis added)

When a reader enjoys a story in a magazine, they have no way of knowing how an interview between a journalist and a source was conducted. Even quotations – which are widely considered being verbatim repetitions of what has been said in the interview – might be very accurate, but they might as well be heavily modified, or even partially trumped-up.

“For journalists, and their editors, **the most important thing is of course to produce a good piece of writing**. This means they might be forced to make compromises, since the citations must serve a purpose for the story,” Lauri Haapanen explains.

The rest of the post goes on to describe “nine essential quoting strategies used by journalists when writing articles”, which is an interesting discussion in itself. But I wanted to point out how fuzzy (or misguided) the statement bolded above is:

For journalists, and their editors, **the most important thing is of course to produce a good piece of writing**.

No.

The most important thing to a journalist is to produce interesting reporting.

Let’s look at the ledes – often considered the part of a story where good writing has (and needs) the most impact – of some published journalism:

Those are the ledes for the winners of what is often considered journalism’s most important prize: the Pulitzer Prizer for Public Service

The

Boston Globe in Sun Sentinel in 2013,

North Carolina, hundreds of miles from America's traditional Midwest hog belt, has become the nation's No. 2 hog producer. Last year, hogs generated more than $1 billion in revenue -- more than tobacco. This year, hogs are expected to pass broiler chickens as the No. 1 agricultural commodity.

One of the five men arrested early Saturday in the attempt to bug the Democratic National Committee headquarters is the salaried security coordinator for President Nixon’s reelection committee.

The District of Columbia's Metropolitan Police Department has shot and killed more people per resident in the 1990s than any other large American city police force.

Bell, one of the poorest cities in Los Angeles County, pays its top officials some of the highest salaries in the nation, including nearly $800,000 annually for its city manager, according to documents reviewed by The Times.

Since the mid-1990s, more than 130 people have come forward with horrific childhood tales about how former priest John J. Geoghan allegedly fondled or raped them during a three-decade spree through a half-dozen Greater Boston parishes.

Here’s a clickbait version:

We've all seen it, and now there's proof: Police officers sworn to uphold our traffic laws are among the worst speeders on South Florida roads.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/gop-security-aide-among-five-arrested-in-bugging-affair/2012/06/07/gJQAYTdzKV_story.html

And here are a couple of ledes from the la times, which, when read in isolation, falls into the “OK is Dunia and why should I give a shit?”

http://www.pulitzer.org/winners/los-angeles-times-3

But “just the facts” isn’t the sole mark of a good

On a warm July afternoon, an impish second-grader named Dunia Tasejo was running home after buying ice cream on her South Los Angeles street when a car sideswiped her. Knocked to the pavement, she screamed for help, blood pouring from her mouth.

I’m being unfair, maybe, because “good” can encompass all of those examples. But that’s my point – “good writing” has no obvious meaning when it comes to journalism or any other form of writing. It is up to the discretion and style of the writers.

But important journalism – journalism that is important to publish. It’s facts.

I went into journalism because I liked writing and am old enough that, when I worked for my college paper, it had enough paper to print 10,000 words, in actual pieces of paper with real ink.

But I don’t think that computers can’t replace a lot of what humans do. They already do – page layout, copy-editing (of the spell-check variety), and research (of the Google-variety) – have all been replaced. Because much of it was mechanical. But the biggest outlets still hire copy editors (also known as fact checkers) and researchers for the bespoke work.

How much of quoting is bespoke work? Depends. I contend that of all the parts of writing that can be automated, it’s one of the least in terms of return on investment.

To describe writing like this:

The Immersive Automation-project focuses on news automation and algorithmically produced news. Since human-written journalistic texts often contain quotations, automated content should also include them to meet the traditional expectations of readers.

No it shouldn’t. That’s one of the things I learned in journalism school: don’t quote parts just repeat someone.

In the development process of news automation, it is realistic to expect human journalists and machines to collaborate.

“A text generator could write a story and a journalist could interview sources and add quotations in suitable places,” says Haapanen.

Also the headline annoys me. It’s not about can. Nor is it about should.

Jekyll websites, open-source and in the real-world

A student hoping to build a project in Jekyll asked me for examples of well-known, well-designed Jekyll sites.

Of course, a site’s visual appearance technically has nothing to do with its framework – e.g. Jekyll vs. Hugo vs. WordPress vs. Drupal, etc. But for folks starting out, important conventions and best practices – such as how to write the template files, which folders to put CSS and other asset files, how to incorporate Bootstrap/SASS/etc., and overall site configuration – are much easier to learn when having source code from sites built with the same framework.

So I’ve compiled a short list (and am happy to take suggestions) of Jekyll sites that:

- Have their source code available to clone and learn from.

- Aren’t just blogs.

- Are attractive.

- Are popular.

Most of these sites have lots of data, content, and words. So they won’t be the most beautiful, in the sense of content-lite sites that feature of chasms of white space and beautiful Unsplash-worthy hero images. But I rate their attractiveness in relation to their function. Most of them are aimed at a general audience (especially the government sites). And many of them have to relay a large array of data and content.

If the official documentation on Jekyll’s data files, collections, and site variables don’t make immediate sense to you, then take a look at these examples’ repos to see how the professionals organize their Jekyll projects.

Templates showcase from Jekyll Tips

OK, most of these templates are geared toward Jekyll’s original use-case: blogs. But front-end assets for Jekyll blogs can be implemented in the same fashion for Jekyll sites that aren’t straightforward blogs. Each of the templates in this showcase have an associated Github repo.

Github On-Demand Training

Since Jekyll itself came out of Github and is used to power Github’s extremely popular Github Pages feature, pretty much all of Github’s static content is done in Jekyll. I’ve tried to list the more notable examples that have their source code available.

Here’s their On-Demand Training page, which is a homepage for their “How-to Use Github/Git” guides, cheat-sheets, and curricula:

https://services.github.com/on-demand/

The repo: https://github.com/github/training-kit

Github’s Open Source Guide

Repo: https://github.com/github/open-source-guide

This isn’t a “complex” site, per se, but it’s a nice non-blog site if you need an example of how to structure a page-based site in Jekyll.

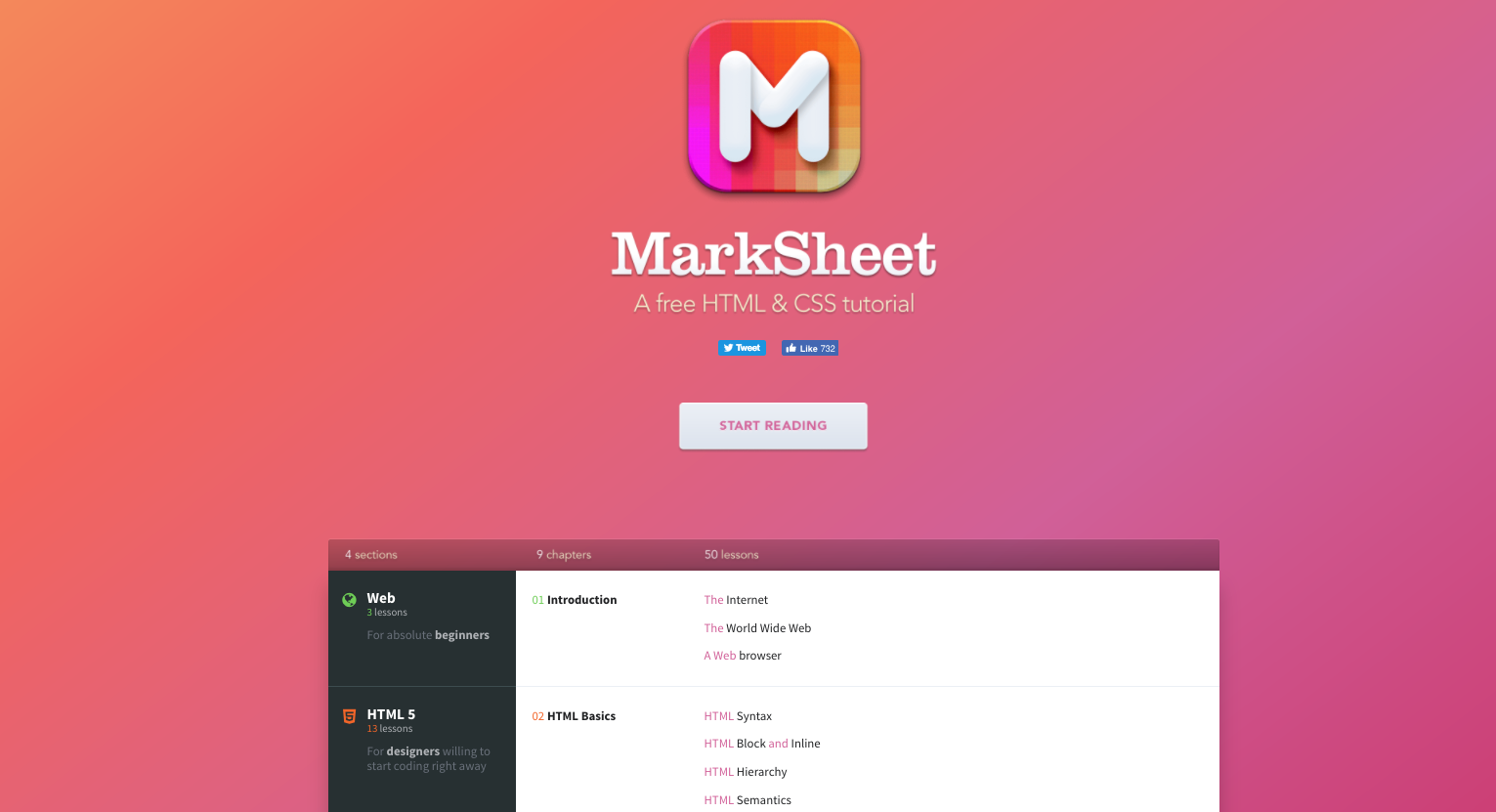

MarkSheet

Repo: https://github.com/jgthms/marksheet

MarkSheet is a free HTML and CSS tutorial site. Nice example of how to structure a Jekyll site to accommodate book-reference-like content.

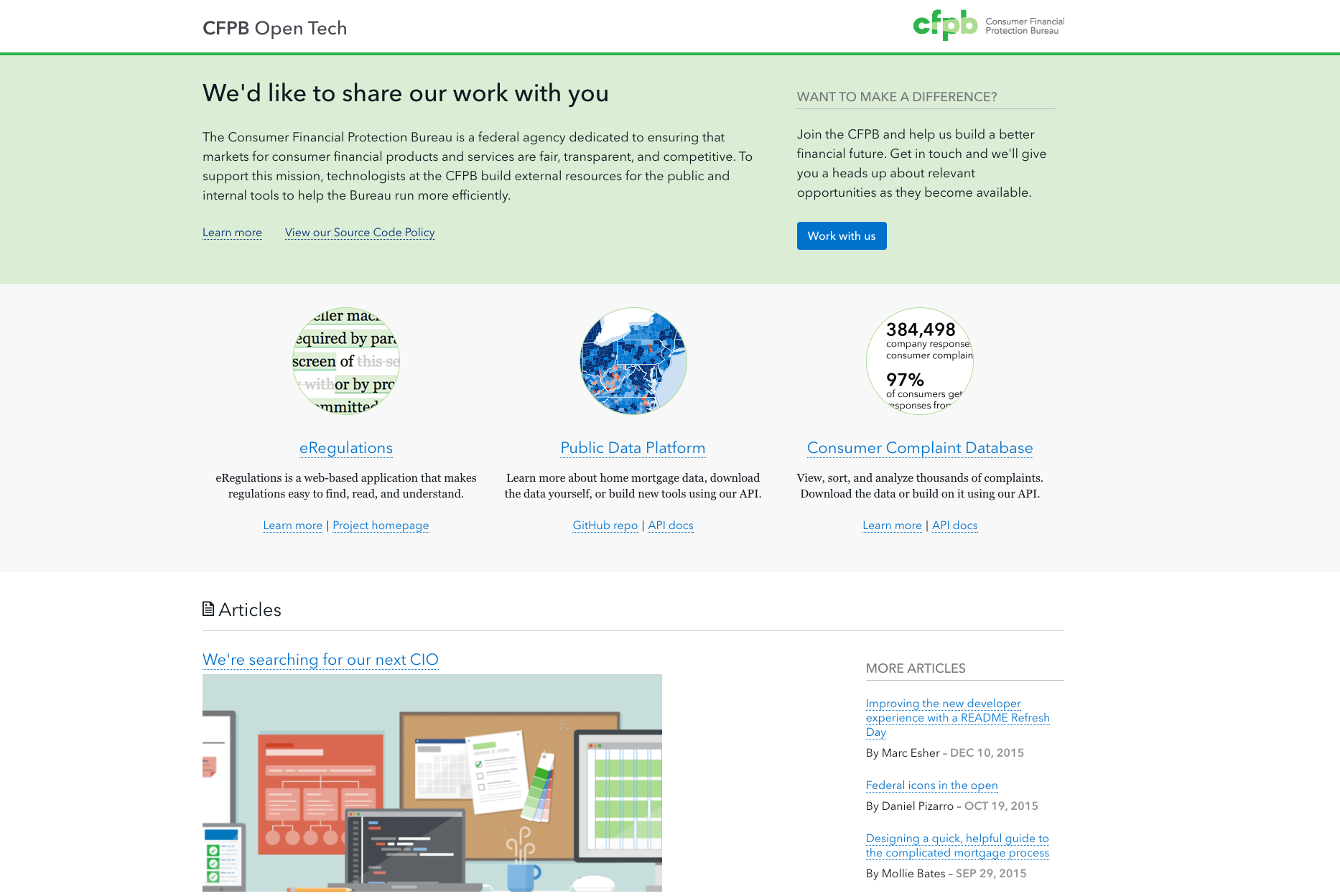

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Developer Homepage

Repo: https://github.com/cfpb/cfpb.github.io

If you want great examples of how to build data-intensive services and sites, there are few better organizations than the CFPB, which, since it’s a government agency, means their work is in the public domain.

Not all of their excellent sites use Jekyll as their front-end (such as the HDMA explorer), but the CFPB’s dev/tech homepage uses it as both a landing page and a blog.

The Presidential Innovation Fellows

https://www.presidentialinnovation.org/

Repo: https://github.com/18F/presidential-innovation-foundation.github.io

The Analytics page for the federal government uses Jekyll to tie together Javascript code for reading from APIs and making charts: https://analytics.usa.gov/

repo: https://github.com/18F/analytics.usa.gov

Our own Stanford Computational Journalism Lab homepage is in Jekyll:

http://cjlab.stanford.edu/

repo: https://github.com/compjolab/cjlab-homepage

Believe it or not, but healthcare.gov – the front-facing static parts, were built in Jekyll: https://www.healthcare.gov/

They took down their source code but here is an old version of it: https://github.com/dannguyen/healthcare.gov

And here’s what that old code produced: http://healthcaregov-jekyll.s3.amazonaws.com/index.html

Here’s a piece in the Atlantic by an open-gov advocate, which is about why healthcare.gov is open source (or was, before the non-Jekyll parts of the site failed to live up to the traffic):

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/06/healthcaregov-code-developed-by-the-people-and-for-the-people-released-back-to-the-people/277295/

18F is the digital agency for the federal government. Much of the modern and best webdev of the U.S. gov is through their shop:

18F’s homepage: https://18f.gsa.gov/ repo: https://github.com/18F/18f.gsa.gov

Their handbook: https://handbook.18f.gov/ repo: https://github.com/18F/handbook

Here’s a post by them about why they switched to Jekyll.

https://18f.gsa.gov/2014/11/17/taking-control-of-our-website-with-jekyll-and-webhooks/

https://stackoverflow.blog/

https://github.com/StackExchange/stack-blog

https://stackoverflow.blog/2015/07/01/the-new-stack-exchange-blog/

https://stackoverflow.blog/2015/07/02/how-we-built-our-blog/

Finding Stories in Data: A presentation to college journalists

This past weekend, I did a quick session at the Associated Collegiate Press Midwinter National College Journalism Convention on how to find stories in data.

You can find a repo with links to my slides and my big list of links here:

https://github.com/dannguyen/acp-2017-finding-stories-in-data

The slides:

It’s not a great or finished presentation, but I’ve been meaning to put together a reusable deck/source list so I can do more of these presentations, so it’s a start. Since this session was for college journalists, most of whom I assume fit the “unknowledgable-of-statistics” mold, I tried to talk about projects that were relevant and feasible for their newsrooms.

In terms of how to get started, my best advice was to join crowdsourcing efforts put on by organizations like ProPublica. Data entry/collection is always a dry affair, but it is always necessary. So it’s all the better if you can find data entry that works towards a good cause. Here’s a few examples:

- Fatal Encounters - Well before Ferguson, this project – started by a single, curious journalist – recognized the severe deficiency of data on police shootings.

- Documenting Hate - ProPublica’s initiative to count hate crimes and bias incidents and create a national dataset.

- TrumpWorld - BuzzFeed has logged more than 1,500 of the Trump Administration’s business and personal connections. Use their spreadsheet and help them find more connections.

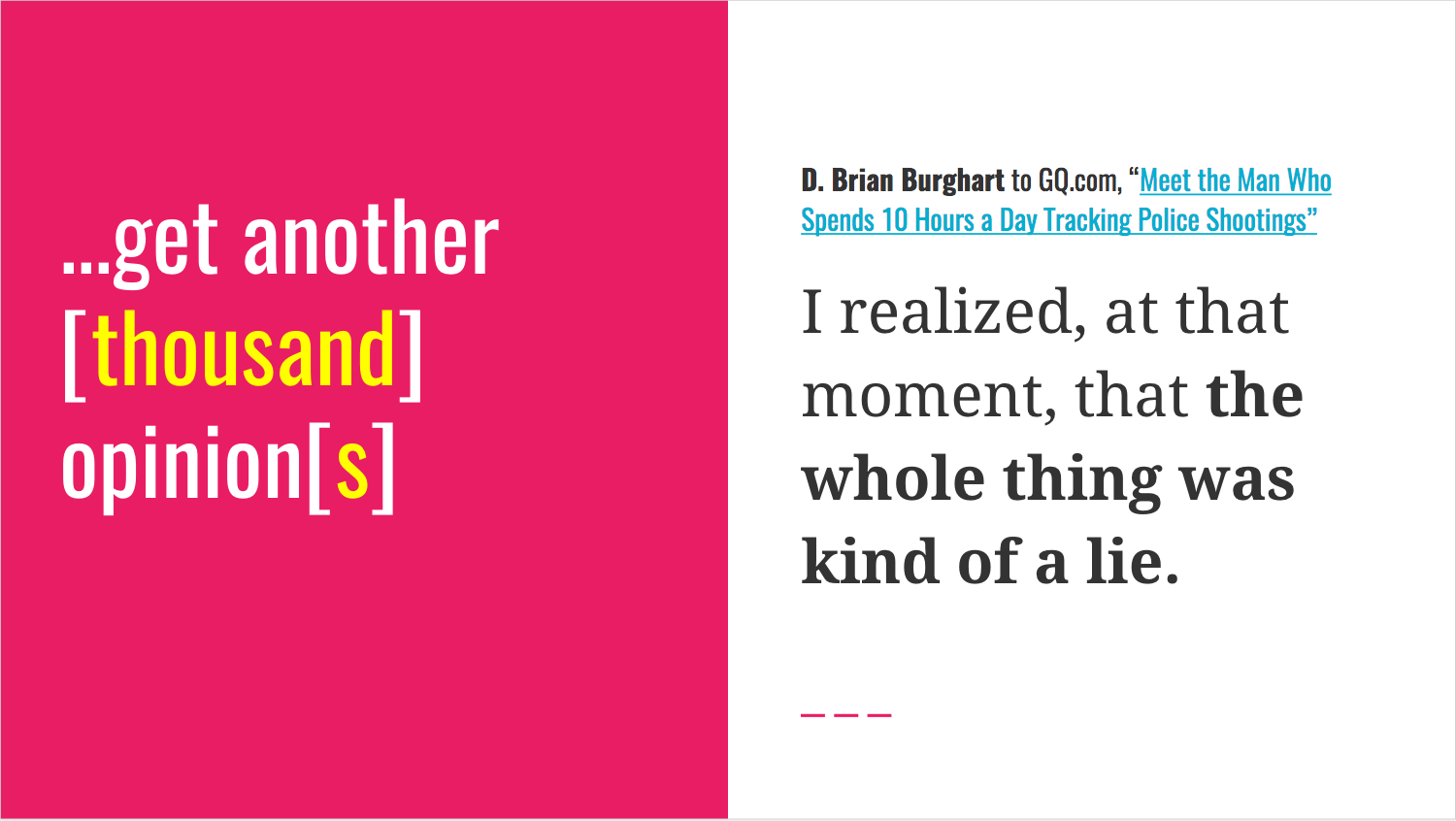

The best insight I found while gathering material was this GQ interview with Fatal Encounters founder D. Brian Burghart: Meet the Man Who Spends 10 Hours a Day Tracking Police Shootings.

Here’s how I documented it in slides:

The main technical advice I gave to students was: Use a spreadsheet for everything. Burghart’s vital contribution to journalism is proof of this method.

subscribe via RSS