The scammers of Harvard Law's Bruce Hay and the "Nigerian Prince" filter

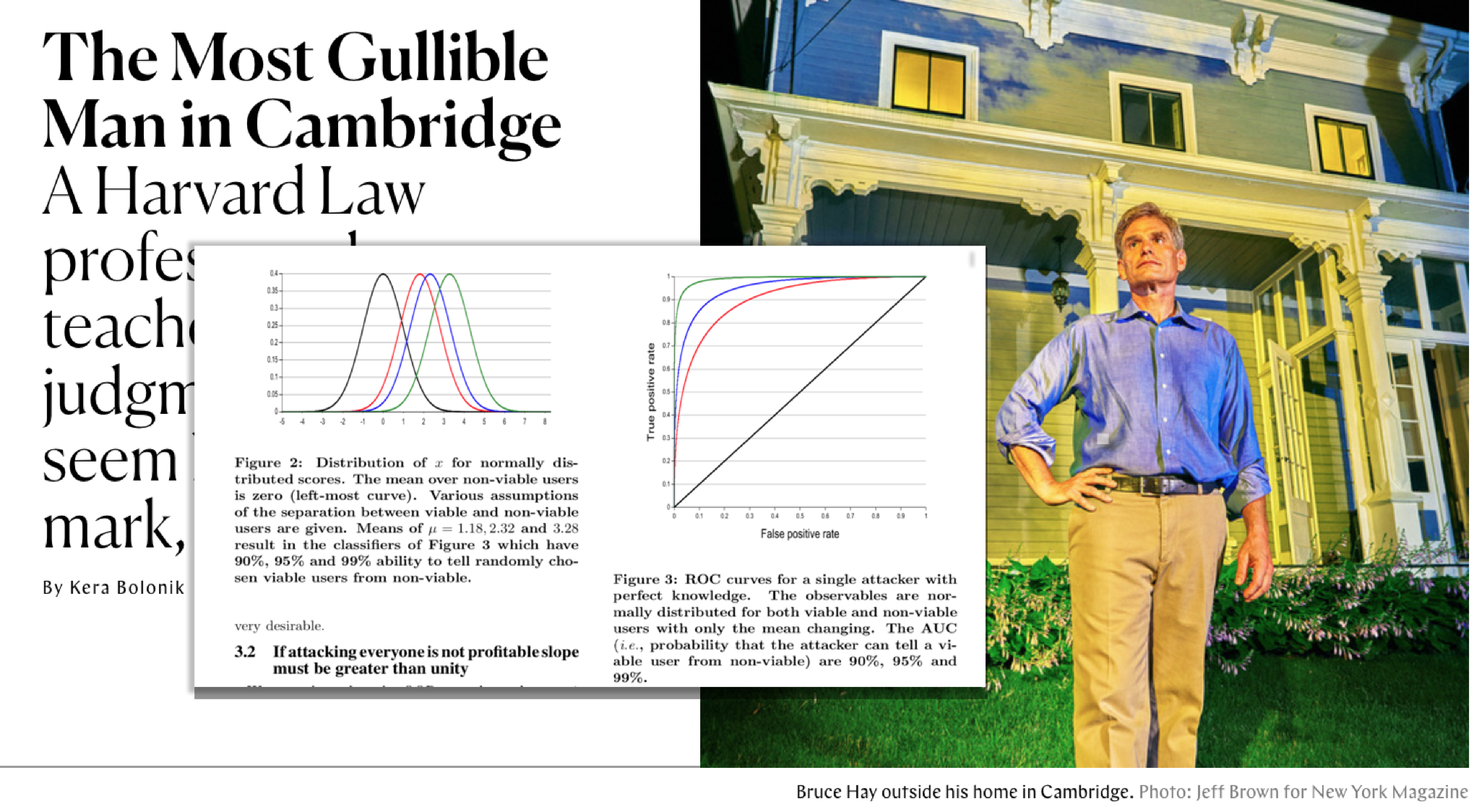

There’s too much to process in “The Most Gullible Man in Cambridge “, the Kera Bolonik longform piece that dropped yesterday on the New York Magazine/The Cut website. For starters, just how completely bananas it is from top to bottom. And then, whether the main character and victim, Professor Bruce Hay of Harvard Law, is a reliable and trustworthy narrator. And of course, the absolute marvel of long suffering patience and wisdom that is his ex-wife (more on that later) and mother of his young children.

Because of its many bizarre elements and threads, Bolonik’s article feels much longer than its 7,000-word count and is hard to summarize. But to do it in one convoluted sentence: Professor Hay is the victim of an alleged paternity scam, one so elaborate it nearly cost him and his family their home, and one that includes sexual misconduct allegations leading to an ongoing Title IX investigation.

The story’s most notable feature is just how gullible and how dumb Professor Hay – who is the on-record source of 90-95% of the narrative – makes himself sound. In this case, a sentence (or several) can’t do Bolonik’s article justice. But one particularly interesting aspect is how seemingly obvious the ploy seems to be, and yet, how it managed to fool several highly intelligent men, including Professor Hay and – as far as we know – three Harvard-area men.

From the story’s first graf, this is how Hay describes his first encounter with the scammer; I’ve added emphasis to the pickup line:

It was just supposed to have been a quick Saturday-morning errand to buy picture hooks. On March 7, 2015, Harvard Law professor Bruce Hay, then 52, was in Tags Hardware in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near his home, when a young woman with long reddish-brown hair approached him to ask where she could find batteries. It was still very much winter, and, once the woman got his attention, he saw that underneath her dark woolen coat and perfectly tied scarf she was wearing a dress and a chic pair of boots — hardly typical weekend-errand attire in the New England college town. When he directed her to another part of the store, she changed the subject. “By the way, you’re very attractive,” he remembers her saying.

In the latter-third of the story, Bolonik writes that Hay and his lawyer uncovered 3 other men who previously filed suit against his scammer. Bolonik met with one of them, who is referred to in court papers as “John Doe”. Here’s how Doe describes meeting the scammer (again, emphasis mine)

This past fall, I met Doe, who told me Shuman appeared out of nowhere at an intersection where he was standing with two colleagues and started chatting him up in what he described as hushed tones. He recalled her saying, “Excuse me, but I couldn’t help but notice that you’re attractive. I’m in town from New York, visiting a friend, and I was hoping you’d be willing to show me around.” He gave her his cell number.

Everything is obvious in retrospect, but here the pickup line, and its contrived circumstances – how many late-20s/early-30s adults show up in Boston or New York without a smartphone to serve as a guide? – seem especially so. How could Doe, described by Bolonik as a “young, lanky, blue-eyed CPA”, or Hay, a tenured professor with nearly 30 years at Harvard Law, fall for something so comically transparent?

Those questions about the depths of human trust and gullibility aren’t readily answered. But I do wonder if the flimsiness of the pickup tactic itself is itself inspired by the trope of the Nigerian Prince email scam, an ostensibly obvious and universally-known scam, yet one that still brings in fortunes for its perpetrators?.

But couldn’t scammers attract even more victims and their money by being more sophisticated? e.g. pretending to be a prince from a country less notorious than Nigeria? In 2012, Microsoft Research’s Cormac Herley studied this question in one of my favorite white papers, Why Do Nigerian Scammers Say They are From Nigeria? (link to PDF).

Here’s an excerpt from the Discussion section (Section 4):

An examination of a web-site that catalogs scam emails shows that 51% mention Nigeria as the source of funds…Why so little imagination? Why don’t Nigerian scammers claim to be from Turkey, or Portugal or Switzerland or New Jersey? Stupidity is an unsatisfactory answer.

It’s a very accessible paper and worth reading, but in summary, Herley argues that the use of “Nigeria” (or “Nigerian Prince”) acts as a very effective filter for the scammer, whose has nearly unlimited bandwidth in the amount of emails sent, but very limited time to deal with “false positives” – i.e. potential victims who ultimately wise up. The percentage of targets who would even open an unsolicited email subject line of “Nigeria” is vanishingly and staggeringly tiny. But the ones who do, Herley argues, are extremely profitable to the scammer:

If we assume that the scammer enters into email conversation (i.e., attacks) almost everyone who responds, his main opportunity to separate viable from non-viable users is the wording of the original email…Who are the most likely targets for a Nigerian scammer? Since the scam is entirely one of manipulation he would like to attack (i.e., enter into correspondence with) only those who are most gullible…

Since gullibility is unobservable, the best strategy is to get those who possess this quality to self-identify. An email with tales of fabulous amounts of money and West African corruption will strike all but the most gullible as bizarre. It will be recognized and ignored by anyone who has been using the Internet long enough to have seen it several times.

It will be figured out by anyone savvy enough to use a search engine and follow up on the auto-complete suggestions such as shown in Figure 8. It won’t be pursued by anyone who consults sensible family or friends, or who reads any of the advice banks and money transfer agencies make available. Those who remain are the scammers ideal targets. They represent a tiny subset of the overall population.

Reading through the Twitter replies to NYMag’s Bolonik, there’s at least one more guy who has a story about the scammer – though apparently, he appears to have avoided the trap:

Hay’s alleged scammer seems to have some of the same constraints as a Nigerian scammer – it’s a huge amount of time and risk to initiate a relationship with a mark who is likely to wise up. So the exceedingly cringe pickup line of “Excuse me, sir, I’mbut I noticed you’re very handsome. Could you show me around New York?” likely had any rejections before finding success in Professor Hay, “John Doe”, and other victims. And this works beautifully for the paternity-test-scammer.

(Note: Except for this aside, I’ve deliberately avoid mentioning or speculating about the motives of Hay’s scammers, which would require an entirely separate wordy blog post. Bolonik’s article offers little revelation. But it’s worth noting that in Hay’s case, unlike with Nigerian scammers, the scammers don’t seem to be primarily motivated by money)

But as with everything else in Bolonik’s necessarily convoluted article, there are only more questions. Herley, the Microsoft researcher, points out that Nigerian scammers depend on victims lacking a support network of “sensible family or friends”. Professor Hay does not seem to be in this situation; he says he and his scammer, before they first had sex, had coffee dates and long talks about their respective lives. She would have learned from him that his ex-wife – who he has 2 children with and who he was still living with, amicably – is an assistant U.S. Attorney. At that point, the ostensibly savvy scammer must have realized that no matter how gullible Hay seemed, or how estranged he might be from the rest of Harvard’s elite, Hay’s ex-wife was definitely going to step in and pursue any scammers who threatened Hay’s (i.e. her) home and children.

And yet here we are. The depths and speed at which Professor Hay fell for the scam is shocking. But it doesn’t explain why (again, assuming that money is not an issue) the scammers would entangle themselves with him, when there are so many other marks. This incongruity (among the many others), added to the fact Hay – against the advice of Harvard and other lawyers – shopped his story around to several other journalists before finding Bolonik, is enough to raise serious doubt that we’ve heard all the relevant and significant facts of this bizarre story.