Facebook Research contemplates the user experience for dead users.

Even if you don’t consider yourself an academic or scientist, Facebook’s research papers are generally great reading if you’re interested in the design decisions behind massive social networks – and their consequences.

Here’s one of Facebook Research’s more universally relevant papers: Legacy Contact: Designing and Implementing Post-mortem Stewardship at Facebook, authored by University of Colorado’s Jed R. Brubaker and Facebook’s Vanessa Callison-Burch, and published last week at ACM CHI 2016.

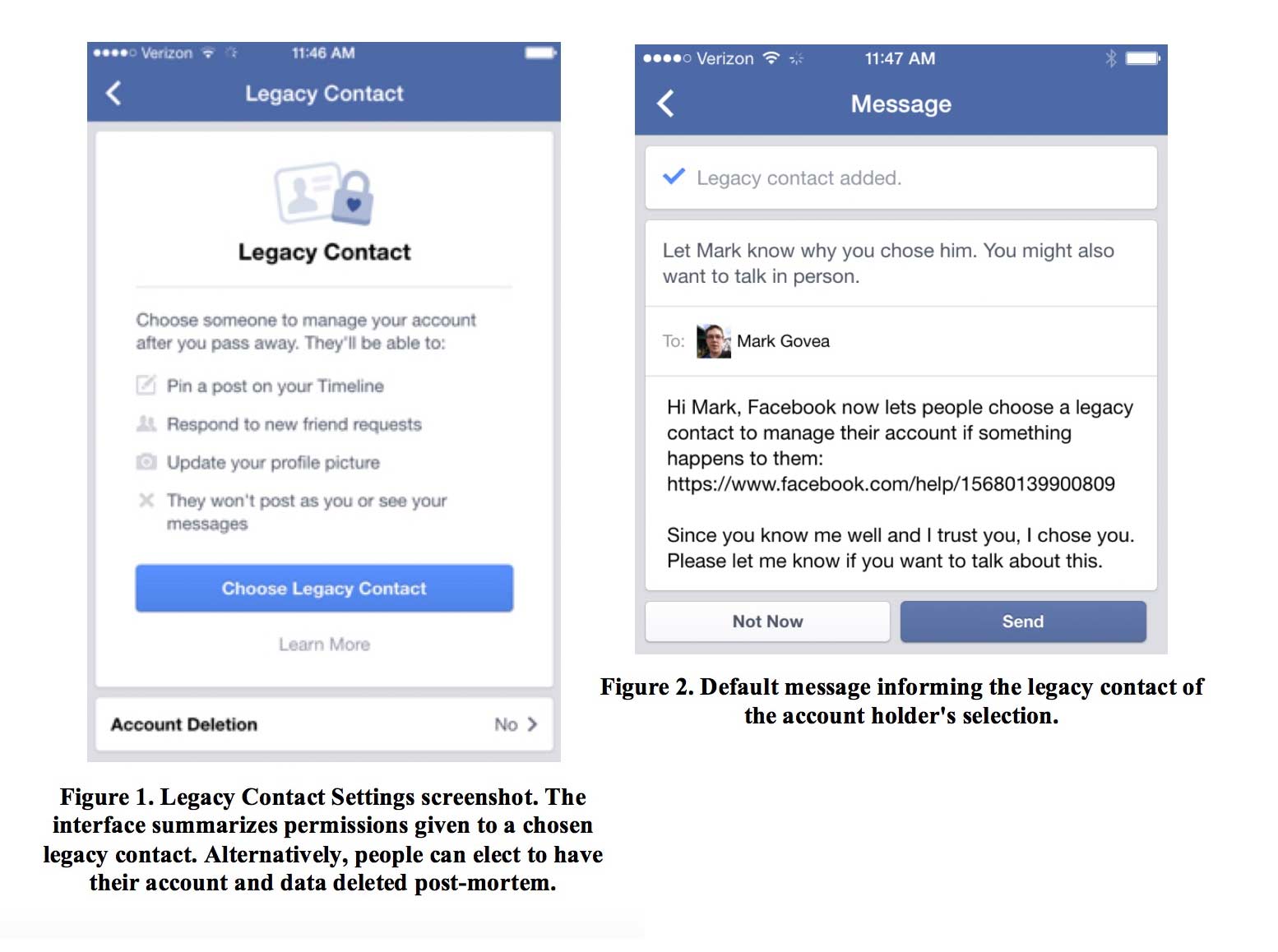

The paper examines the design decisions (and precedents) for Facebook’s Legacy Contact feature, which was introduced on February 12, 2015. A “Legacy Contact” is someone you designate to be the caretaker for your Facebook account in the event of your death. Like writing a will, how your account is maintained is a decision you have to make before you die – but Facebook’s implementation is more complex and nuanced than the analogue of real-world inheritance.

Back in 2007, Facebook introduced the ability to “memorialize” an account after its holder’s death, which would essentially lock down the account’s content and privacy settings as they were before the user died.

But what if you died before really thinking about how your Facebook profile would appear for perpetuity? Facebook claims its Community Operations team has responded to “every request about memorialization”, but there were apparently a few fairly common but “surprisingly complex” situations that had no easy answer. For example, if you avoided friending your parents because that’s just not cool to do, then in the event of your unexpected death, your parents would be forever blocked from sharing (and even viewing) memories on your Wall.

Despite Facebook’s massive amount of data on its users, it admits it can’t (or at least, would rather not) predict a user’s preferences after death, such as whether or not a user’s non-friending of their parents was for trivial reasons or actual reasons:

While it might intuitively seem like Facebook should fulfill these kinds of requests, Facebook has no way of knowing what a deceased person would have wanted. Did that son want to be friends with his father on Facebook? And who gets to decide if a profile photo is or is not “appropriate?”

These are choices that are made by account holders while they are alive, and Facebook respects those choices. In the absence of the deceased account holder, and given the changing needs around profiles post-mortem, we looked for ways to improve how Facebook supports grieving communities.

Further down in the paper, under a subhead of “Privilege human interaction over automation”, the paper’s authors point out that the maintenance of these deceased accounts is one situation in which automation is not desirable:

Earlier research found that automated content and notifications can result in confusion and concern for the well-being of the account holder. Moreover, end-of-life preferences are often nuanced and contextual. As such, we sought to reduce automation where possible and encourage interpersonal communication rather than rely on Facebook notifications and configuration.

(Automation has previously caused problems when it comes to death; see Eric Meyer’s essay on “Inadvertent Algorithmic Cruelty”.)

Because of their scale and the digital infrastructure on which they operate, social networks have challenges and complications that don’t apply in the physical world. I imagine that Facebook’s relatively young demographic – particularly its general unawareness and non-anticipation of death – also exacerbates the issues in deciding the access control for a dead user’s account.

The authors of the paper write that Facebook considered three approaches on how to handle post-mortem data. I’ve summarized them as:

| Approach | Description | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Configuration | Define what the system should do when you die, such as posting a final Wall post that you’ve (hopefully) written. | When’s the last time you updated your “Final Wall Post” to include all the people and things you truly care about? When’s the last time you did do while being sober? |

| Inheritance | Designate an “heir” to login and take over your account. | Your “heir” gets to see all the private data you hadn’t realized would be included in the “inheritance”. |

| Stewardship | Designate someone to take care of the account, but not “own” it or its data | Trust Facebook to design the right balance between features and limitations. |

Facebook went with the stewardship-based route, which requires more thought and work from them. On the other hand, it ultimately provides more flexibility and granular access control than the other two approaches.

Even as an avid, considerate Facebook user, you might be surprised at all the design decisions that have to be made in creating an effective “stewardship” role for Facebook accounts, such as: how do you (the account holder) explain to your Legacy Contact why you chose them to be your Legacy Contact? And: should a dead user’s friends get notifications when a Legacy Contact makes changes to the dead user’s profile?

One interesting design nuance that I hadn’t considered: While a Legacy Contact is allowed to add friends to the deceased’s account, the Legacy Contact cannot remove the friends that the deceased had added during their lifetime, “in the name of preserving the profile as created by the deceased.” So, defriend people as if it were your last day to defriend…

The full paper (10 pages, not including its list of references), which was accepted at the Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, can be found at Facebook Research:

Or on ACM:

http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2858254&CFID=613872472&CFTOKEN=61242498&preflayout=flat

Sidenote: I love the line that’s prepended to the paper’s abstract, as viewed on the Facebook Research site (emphasis added):

This is a descriptive paper, not a research paper that is based on any experiments. In this paper we describe Legacy Contact, a new feature that better supports people coping with the death of of a loved one on Facebook while giving people more control over what happens to their Facebook account in the future. Following a user’s death, how can social media platforms honor the deceased while also supporting a grieving community?

In this paper we present Legacy Contact, a post-mortem data management solution designed and deployed at Facebook. Building on Brubaker et al. (2014)’s work on stewardship, we describe how Legacy Contact was designed to honor last requests, provide information surrounding the death, preserve the memory of the deceased, and facilitate memorializing practices. We provide details around the design of the Legacy Contact selection process, changes made to memorialized profiles, and the functionality provided to Legacy Contacts after accounts have been memorialized. The volume of post-mortem data will continue to grow and so it is important to take a proactive approach that serves the needs of both Facebook users and their community of friends.

Given past reaction to Facebook experiments, it’s probably (very) wise for Facebook to anticipate that the average person (and tech reporter) might jump to morbid conclusions when seeing something about dead Facebook users under the umbrella heading of “Facebook Research” and to preemptively state this paper didn’t involve any A/B-type experiments on users.